Clean and Unclean

Ritual Purity in the Worship of God

by Jeffrey J. Harrison

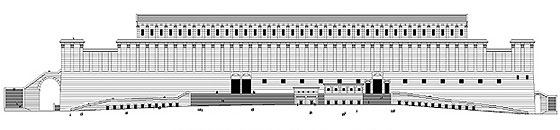

The Jewish Temple in the time of Jesus was an awesome structure. The true size of it only dawns on you when you stand by one of its building stones. Most were a uniform 4 ft (1.2 m) in height and up to 35 ft (10 m) in length of precisely cut limestone. The smaller stones were 30-50 tons each. The largest yet found is 10 by 43 ft (3.5 by 14.5 m), with an estimated weight at between 400-600 tons—for a single stone! Yet these stones fit so precisely, without mortar, that only where there has been erosion or other damage can you squeeze a slip of paper between them.

The walls originally went soaring straight up as much as 120 ft (37 m) above the surrounding street level. These were support walls for an elevated platform and buildings within. This platform (the Temple Mount) encloses a rectangular area of 35 acres (14 hectares) in size.

In the middle of the enclosure, the sanctuary building rose above the rest, its gold-covered roof glowing like fire in the rays of the desert sun. Josephus, the Jewish historian, wrote, To approaching strangers [the Temple] appeared from a distance like a snow-clad mountain; for all that was not overlaid with gold was of purest white

(Jewish Wars 5.5.6 § 223). The rabbis said that whoever has not seen the Temple has not seen a beautiful building (B.B. 4a:6). Jesus’ disciples agreed: Look—what wonderful stones and what wonderful buildings!

(Mark 13:1). Both in its conception and its realization, this was an image of heaven, of coming into the presence of God himself (Heb. 9:23-24).*

* Herod the Great, whose improvements to the Temple we are describing, is said to have consulted the prophetic plan of Ezekiel for guidance in his design (Eze. 40-44, Middot 2:5, 3:1, 4:1-2).

The main entrance to the Temple Mount was on its south side. Here, behind a plaza lined with shops, rose a 244 ft (75 m) wide stairway approaching the southern façade of the Mount. This huge stairway is sometimes called the stairs of the rabbis

in memory of Rabbi Gamaliel and the elders, who would sometimes sit here to make religious rulings.* This is the same Rabbi Gamaliel under whom the apostle Paul studied, and who defended the early Jewish Christians before the Sanhedrin Council (Acts 5:34, 22:3). This stairway led to two sets of gates

—31 ft (9 m) high doorways in the façade. These opened into tunnels which then led to stairs up to the Temple Mount platform above.

* Tosefta Sanh. 2:6, Sanh. 11b:2.

Access through these gates was restricted to those who were ritually clean. This was the reason for one of the small buildings built right into the middle of the stairs of the rabbis

(see drawing above). It was filled with dozens of Jewish ritual baths (known in Hebrew as mikvaoth [mik-vah-oat], or mikveh in the singular). These were not used for cleaning off dirt, but for a special ritual immersion. This building sent a clear message: that ritual purity is required for the worship of God.*

* The discovery of these baths solved the problem of where the thousands of Jewish worshippers were baptized that accepted Jesus on the Day of Pentecost (Acts 2:41). Additional ritual baths have since been discovered nearby. It may have been here that Mary was immersed after giving birth to Jesus when she came to offer up the required sacrifice in the Temple (Luke 2:22-24).

These ritual baths could not be filled with a bucket. They had to be filled with living

(naturally flowing) water. For the baths at the entrance to the Temple, this meant rainwater—water from heaven—that had fallen on the Temple itself. This was then channeled into the baths themselves, providing a heavenly cleansing.*

* This was also the symbolism of the bronze Sea,

the large mikveh of the priests that once stood before the entrance of the sanctuary building. In Solomon’s day, this huge basin was held up by twelve bronze oxen (1 Kings 7:23). They represented, in the style of the day, angelic creatures holding up the sky, just as the four living creatures in Ezekiel held up the firmament

(Eze. 1:22; the same Hebrew word that appears in Gen. 1:6-8). When the priests washed their hands and feet in this water before entering the Sanctuary, they washed in the water of heaven (see Gen. 1:7, Deut. 28:23).

What kind of uncleanness

made such a bath necessary? It could come from many different sources. The highest degree of uncleanness is a dead body (known by the rabbis as a father of the fathers of uncleanness

). Anyone who touches a dead body or is in a room with a dead body is made unclean for seven days (becoming a father of uncleanness,

Num. 19:11,14). Other sources of ritual impurity include a woman in her time of the month (also a seven day uncleanness, Lev. 15:19), a woman who has given birth (a forty day uncleanness if to a baby boy, eighty days for a girl, Lev. 12:2-5), marital relations of a husband and wife (a one day uncleanness, Lev. 15:18), and touching an animal—or even an insect—that has died (unless the animal died from a ritually clean slaughter, Lev. 11:24-42). Lesser degrees of impurity derived from these: for example, from touching something that had been touched by an unclean person (a one day uncleanness; Lev. 15:22, Num. 19:22).* But all of them barred you from entry into the Temple.**

* Additional sources of uncleanness were decreed by the scribes and the Pharisees. But several of these additions are rejected in the New Testament. The apostle Peter, for example, once observed the rabbinical decree that made Gentiles unclean. But he changed his mind when God showed him in a vision that he should not call any man unholy or unclean

(Acts 10:28).

Another Pharisaic decree, that Samaritans were unclean, was rejected by Jesus when he asked the Samaritan woman at the well for a drink. He knew that her pot would be considered unclean because of her contact with it (John 4:7,11,28). But this was one of the rabbinical rulings that he considered a tradition of men,

in opposition to the revealed Word of God in the Bible (Mark 7:8).

The most well known of the Pharisaic decrees challenged by Jesus was the requirement that hands be ritually washed (netilat yadayim). This ruling was established in the preceding generation of Hillel and Shammai (Mark 7:3,5). For more on this subject, see our teaching Did Jesus Abolish the Jewish Food Laws?

** Until the given time had passed and you had taken the necessary steps to become clean again. One of the most important of these steps was taking a ritual bath. For more information on ritual baths see our article The Baptism of Jesus. Contact with the dead also required a ritual sprinkling twice during the week of uncleanness with water mixed with the ashes of a red heifer (Num. 19:16-19).

But although the Bible is clear about what made a person unclean, it’s not always clear about why these things were unclean in the first place. Why, for example, is a woman who has just given birth impure (Lev. 12:2)? And why would that keep her from coming into the presence of God for public worship?

The answer—or at least the first part of the answer—is that just because something is ritually unclean doesn’t necessarily mean it’s morally bad or wrong. Burying the dead, for example, was considered an important religious duty, important enough to risk your life to do (Tobit 1:17-19). So why is it considered unclean? The Bible doesn’t say directly. But all the sources of uncleanness mentioned in the Bible have one thing in common: they all involve contact with death.

Man-made religion insists that death is a natural part of life. In some cases, pagan religion even glorified human death: human sacrifice was practiced even by some of the kings of Judah (2 Kings 16:3, 17:17, 21:6, 23:10). But the message of the Bible is that death is an enemy that will ultimately be overcome (1 Cor. 15:26). Death is the opposite of life; it’s the opposite of the life-giving power of God. As a result, all contact with death is clearly marked off in the Bible to distinguish it from the presence of God.

But how does this apply to giving birth? How can fulfilling God’s command to be fruitful and multiply

be a source of uncleanness (Gen. 1:28, Lev. 12:2-5)? Even in modern first-world countries, the pall of death sometimes hangs over pregnancy. Certainly in ancient times, and even recent history, women often died in childbirth. Even in a normal birth, the blood released is a reminder of death, since the Bible teaches that the life is in the blood (Lev. 17:11).

What about the marital relationship of a husband and wife? How can that be considered unclean (Lev. 15:18)? There is no shedding of blood and no contact with death as we ordinarily think of it. But even here, most of the seed of the man dies, even when a conception takes place. So, too, when conception does not take place, the seed of the woman dies.

Many pagan religions glorify the sexual relationship, including modern secularism. In ancient times, immoral relations were actually part of the religious ritual in certain pagan temples. But God pronounced the sexual relationship unclean even for a man and wife, an uncleanness that restricted entrance to the Temple. Yes, the marriage relationship is something godly and good, but it is distinct from the life-giving presence of God.*

* This can be seen in the exclusion of marriage from the resurrection (Matt. 22:30). Although some groups teach marriage and the production of babies in the Millennium, this is one of the earliest heresies rejected, according to the Church fathers, by the apostle John himself (the heresy of Cerinthus; Eusebius, Church History 3.28; Irenaus, Against Heresies, 3.3.4).

As a result, uncleanness cannot always be avoided. Even some of the required ritual duties of the priests made them unclean. These were ceremonies that God himself had commanded, such as burning the Red Heifer (Num. 19:7) or leading out the scapegoat (Lev. 16:26). But since they involved contact with sin and death, they were clearly marked out as unclean, and barred entry to the Temple until purity was restored. Death was not to be confused with the life-giving presence of God.

The Gentile Church has often misunderstood the Bible’s teaching about clean and unclean. From an early date, the bones of martyrs were treated as holy relics, and churches turned effectively into cemeteries of the dead.* But while the death of the martyrs as a testimony to the faith is unquestionably godly and good, this doesn’t change the fact that the bodies of the dead are unclean. The Bible doesn’t consider death itself a good thing, or even a natural event, but rather an enemy, a result of sin, that will one day be destroyed (Rom. 5:12,21; 1 Cor. 15:26,54; Rev. 20:14).**

* This despite Jesus’ rebuke of those who build and decorate the tombs of the righteous (Matt. 23:29-32). The same psychology lies behind the use of crucifixes (which have an idol of Jesus hanging on the cross). Another example is the pagan practice continued by early Gentile Christians of eating in cemeteries in memory of the dead—a practice that can still be seen today in All Saints’ Day celebrations in many countries, where meals are eaten in the cemetery.

** This is why physical resurrection was such a central and essential part of the apostolic teaching, though in later centuries it was often neglected as a living doctrine. After all, if death itself brings us into a satisfactory permanent condition with God, how can it be considered bad? And what need is there of a resurrection? Yet the souls in heaven are not content, but cry out, How long, holy and true Master, will you not judge and avenge our blood on those dwelling on the earth?

(Rev. 6:10). The drama of history is not resolved, and the future of mankind is not achieved without a physical resurrection and just retribution for the deaths of the martyrs.

This misunderstanding of clean and unclean also underlies the historical shift in meaning of the Lord’s Supper. This sacred memorial of Jesus’ last Passover and death was first introduced at a Passover Meal, in which many of the food items on the table had traditional symbolic meanings (Matt. 26:19).* Jesus used these same food items as symbols of his impending death and of the covenant established by his blood.** But this beautiful teaching, once removed from its original Jewish context, was misunderstood and turned into the strange idea of eating, supposedly, the actual dead body of Christ. This is the Roman Catholic teaching that the priest sacrifices Jesus anew in the communion service (as a bloodless sacrifice

) and that the bread and wine of communion turn physically into the actual body and blood of Christ (the doctrine of transubstantiation).

* Unleavened bread, for example, represents the haste with which the Israelites had to leave Egypt, leaving no time for their bread to rise (Exo. 12:39). Lamb was eaten in memory of the lamb whose blood protected them from the angel of death in the plagues (Exo. 12:13). Salty water represents the tears of the children of Israel in slavery in Egypt; baked eggs represent the hardness of Pharaoh’s heart, and so on. See our downloadable Christian Celebration of the Passover Meal booklet and Passover Preparation Instructions.

** Jesus’ words of blessing are often misunderstood as a blessing of the bread and wine themselves (Matt. 26:26-27). But Jewish blessings, then as today, are always directed to God: Blessed are you, Lord our God...

The earliest surviving version of the invocation of the Holy Spirit in the Eucharistic Prayer (the Epiclesis) called not for the Spirit to change the bread and wine, but rather to fill and strengthen the believers gathered for worship (Apostolic Tradition 4.11-12).

But despite their good intentions, these changes to the ceremony violate the Bible’s teaching about clean and unclean, claiming to bring a dead body right into the heart of Christian worship. But Scripture considers it an act of apostasy to again crucify...the Son of God, and put him to open shame

(Heb. 6:6). Rather than being a continual sacrifice, Jesus tasted death once for all (Heb. 9:12,28). Then he rose from the dead, never to die again (Rom. 6:9). As the empty tomb in Jerusalem proclaims: He is not here; he has risen (Matt. 28:6)! The communion service he instituted doesn’t benefit us because of any substance in his dead body that we could take in by chewing on it. Rather it benefits us because it’s a reminder and a renewal of the covenant promise of God to forgive sin so that we, too, may rise with Jesus.

Many of the Biblical laws of clean and unclean are no longer in effect among the Jewish people because of the destruction of the Temple.* But the laws of ritual purity continue to provide us with important lessons. One is that in God himself there is no spiritual uncleanness or death; the presence of God is the opposite of death. Another is that in this life, we can’t always be worshipping in the Temple. There are times when we, like Jesus, are called to make contact with those who are lost in the darkness of sin and death in order that we might bring them to the light. But while this and other necessary actions may keep us for a time from public worship, we are also called to be cleansed once again with a spiritual cleansing, a baptism (an immersion) in the Holy Spirit, the true living water

from heaven, so that we might enter the Temple of God’s presence again (John 7:38; Titus 3:5).

* As they are understood to be concerned only with entrance to the Temple. The Temple was destroyed by the Romans in AD 70 in the First Jewish Revolt against Rome.

Have you been made clean by the living God? Have you been immersed in the water of life? Have you entered his gates with thanksgiving, and his courts with praise (Psalm 100:4)? Lord, draw us into your sanctuary that we might worship you in purity of heart. Help us experience more of your life-giving presence!

-------------------

The diagram of the southern Temple façade above follows the reconstruction of Leen Ritmeyer in Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount in Jerusalem (Washington D.C.: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1990), pp. 36-37.

Recent illegal construction on the Temple Mount has destroyed archeologically priceless information about the Jewish Temple. To learn more about this desecration of one the world’s most important cultural and religious sites, visit The Temple Mount Sifting Project.