The Messianic Judge

Jesus’ Message at Nazareth

by Jeffrey J. Harrison

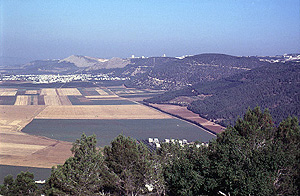

Unlike the dusty desert colors of Jerusalem, Galilee is fresh, green, and beautiful. Orchards and fields lie everywhere; the silvery leaves of olive trees shimmer with every passing breeze. The village of Nazareth, where Jesus grew up, is right in the heart of Galilee, up on a long hill known today as the Nazareth Ridge.

From below, Nazareth lies hidden, nestled in a hilltop valley. But from above, the view is magnificent. From the north rim of the valley above the town, you can see, if it’s clear, all the way to snow-capped Mt. Hermon. From the south rim, atop a rocky cliff, you can see out over the Jezreel Valley and all the way to Mt. Carmel, where Elijah faced the prophets of Baal.

This southern peak, now a public park,* provides a commanding view over what has been a battlefield through the ages. Here Deborah and Barak faced the Canaanites, and Saul battled the Philistines. To the southeast, Gideon fought the Midianites. To the west, King Josiah battled Pharaoh Neco. Across the valley, Jezebel was thrown down from her palace window, and from west to east across the entire view Elijah outpaced King Ahab’s chariot. Imagine the interest that would put into a Bible study lesson: taking a group of young students on a hike up to this magnificent view and pointing out the very sites where so many dramatic Biblical events took place. Jesus certainly had this experience as a boy, if not with his family, then on an outing with his class at synagogue school.

* Known as the Mt. of Precipitation, Mt. Precipice, or Mount Kedumim.

Huge armies marched through this valley over the centuries—from the Assyrians and Babylonians of old to the army of Alexander the Great; and more recently Crusader and Moslem armies, even Napoleon and the British under General Allenby. All either fought in this valley or passed through it. But its days as a battlefield are not just in the past. The book of Revelation calls this the valley of Armageddon,* and says it will be the staging area for the final war of the nations against God and his Messiah (Rev. 16:16). The nations, though, will be at a serious disadvantage: they’ll be in Messiah’s home turf.

* In Hebrew, Armageddon means the mountain of Meggido.

Meggido was one of the Canaanite cities at the edge of the valley that confronted Joshua and later Deborah and Barak.

The spot from which we have had this magnificent view came close to being the place of Jesus’ last breath. It was late on a Sabbath morning when he was marched out to this rocky viewpoint to be thrown down into the valley below (Luke 4:29).* Why? What had he done? His sermon that morning had so upset his fellow townsmen, they had decided to put him to death. What had offended them? He had compared them to the generation of Ahab and Jezebel, a generation for which God did no miracles because of its idolatry and disobedience (Luke 4:25-27).

* This gives the rockly cliff it’s name: the Mount of Precipitation. This refers to the precipitation of a headlong fall, which Jesus nearly experienced here. The identification of the site is traditional, but is supported by its steep slope and proximity to the ancient village.

This was not the kind of teaching they wanted to hear. They were looking for a Messiah that would fight against their Gentile enemies, not one that would judge fellow Jews! By what right did Jesus speak like this to them? To their minds, only God is able to judge the hearts of men. And since they didn’t accept that Jesus was God, his words were blasphemy in their ears.

The penalty in the Bible for blasphemy is death by stoning (Lev. 24:14-16). But by Jesus’ day, this was done by pushing the victim off a high place.* This was probably for humanitarian reasons: stoning can be a long and painful way to die.** If the fall didn’t do the job, then a large stone was dropped on the victim’s chest. And if that didn’t work, everyone standing by would pick up stones and throw them until the deed was done (Mishnah, Sanhedrin 6:4).

*This may be how Stephen, the first Christian martyr after Jesus, was killed (Acts 7:58). The tradition persisted for years that he died outside the north gate of Jerusalem (not the eastern St. Stephen’s Gate shown today). Here, not far from today’s Damascus Gate, there is a steep, rocky cliff. This may have been the city’s ancient place of stoning (the site of today’s Garden Tomb and the adjoining bus station). This explains, too, why James, the brother of Jesus, was pushed down from a high place as the first step in his execution (Eusebius, Church History 2.23).

**A stoning at Jeddah in February 1958 went on for more than an hour before the victim was dead.

But after Jesus and the angry crowd came near the edge of the cliff, the crowd suddenly parted and he walked away (Luke 4:30). Why did they let him go? The Bible doesn’t explain what happened. But someone recently noticed that the distance from the edge of the cliff to the village is more than a Sabbath day’s journey (the maximum distance permitted for travel on the Sabbath: a little over half a mile). Had his opponents made it to the edge of the cliff, they, too, would have committed a crime worthy of death. But whether for this reason or some other, Jesus’ death was postponed to another time.

But this experience didn’t stop Jesus from pronouncing judgments: Woe to you, Chorazin! Woe to you, Bethsaida!... It will be more tolerable for Tyre and Sidon [pagan, Gentile cities] in the day of judgment than for you...

(Matt. 11:21,22). He also judged Jerusalem for its wickedness and prophesied its destruction (Matt. 23:37-38; Luke 19:42-44).

Why was this so controversial? In the Bible and in Jewish society, judgment was understood to belong to God. Human judges were considered agents of God, exercising a holy office. This is why the seventy judges appointed by Moses in the desert had the Holy Spirit poured out on them: to help them exercise their office (Num. 11:16-17,25). In the same way, the seventy member Sanhedrin Council, the institutional descendant of these early judges, was believed to exercise divine authority: Messianic prophecies were occasionally applied to it by the rabbis (Psa. 89:38 in Ecclesiastes Rabbah 12:7, in Judah Nadich, The Legends of the Rabbis I, 1994, p. 166).*

*There were seventy members in the Sanhedrin plus the high priest acting as president of the council. The composition of the council is described somewhat differently by the rabbis than by Josephus and the New Testament. But all agree as to the basic size and authority of this council.

This is why the kings of Israel, who also served as judges, were anointed for office, and sometimes referred to as sons of God.* Unlike our modern separation of the judiciary from the executive branches of government, judgment was considered a right of kings, and one of their chief duties. This explains the title of the seventh book of the Bible: the book of Judges. These were not judges in the modern sense, but military leaders whose victories demonstrated God’s approval and gave them the right to judge disputes.

* In prophetic anticipation of the Messiah (Ps. 2:7, 89:26,27).

So for example, when Jesus says, in Matthew 19:28, that the twelve apostles will sit on twelve thrones judging the tribes of Israel, this means that they will be the anointed rulers over the twelve tribes of Israel. In the same way, when Paul says that the believers in Messiah will judge the world, this also means they will be the God-ordained rulers of the world (1 Cor. 6:2, as in Rev. 20:4).

Given this understanding, it’s only natural that the Messiah, too, as the Lord’s anointed king, has the right to judge. In Micah 5:1, the Messiah is called the judge of Israel

. But far from being an ordinary human judge, his divine nature is also hinted here: his origins are from of old, from the days of eternity

(Micah 5:2).

The same understanding can be seen in Isaiah 11, another famous prophecy of the Messiah. Here, one of the primary responsibilities of the Messiah is to judge the people: With righteousness he will judge the poor, and decide with fairness for the afflicted of the earth

(Isa. 11:3,4). For this he is given the anointing of the seven-fold Holy Spirit: The Spirit of [1] the Lord will rest on him, a Spirit of [2] wisdom and [3] understanding, a Spirit of [4] counsel and [5] strength, a Spirit of [6] knowledge and [7] the fear of the Lord

(Isa. 11:2). This prophecy was fulfilled when the Spirit descended on Jesus at his baptism: a sign that he, as the Messianic king, is anointed to judge justly.

One of the verses in this section posed a puzzle for the early rabbis. How can the Messiah judge, they asked, if he does not judge by what his eyes see

(Isa. 11:3)? The answer is provided in the book of Revelation: the lamb has seven eyes, which are the seven spirits of God sent into all the earth

(Rev. 5:6). The Messiah (the lamb) will judge by the eyes of the Spirit—described with the same seven-fold nature as in Isaiah 11.

But this will not be the quiet judgment of a courtroom. The Messiah’s jurisdiction extends to the day that God will judge the earth: the Day of the Lord, in which the wicked will be destroyed. In that day, the Messiah will strike the earth with the rod of his mouth

(Isa. 11:4); he will destroy the nations in rebellion against God. Since the office of king and judge are one, this righteous warfare against the nations will also be a judgment of those nations.

Psalm 2 uses the same image of judgment: the rod

of the Messiah will strike the nations, smashing them like pottery

(Psa. 2:9).* Here the Messiah is called the Son of God with words similar to those quoted by the Father himself over Jesus at his baptism: You are my Son

(Psa. 2:7; see Matt. 3:17, Luke 3:22, etc.). This is followed by a prophecy of the universal reign of the Messiah—with a hint to the salvation of the Gentiles (the nations): Ask of me, and I will give nations to be your inheritance, and the ends of the earth to be your possession

(vs. 8).

*The word often translated Anointed

in Psa. 2:2 is the Hebrew word for Messiah.

In Isaiah 51, God’s judgment is accomplished by his arms

: My arms will judge the peoples and for my arm they will wait expectantly

(Isa. 51:5). The two arms of the Lord, together with the Lord himself, are a beautiful picture of the tri-unity of God. But the Father is now hidden from us because of our sin. This is the message of the Temple with the ark of God hidden behind a curtain (your Father in secret,

Matt. 6:6). If he were to reveal himself now, in the fullness of his holiness, we would all be destroyed (man cannot see me and live

Ex. 33:20). But because of his great love, he is reaching out to us with his arms—the Son and the Spirit—which he uses to draw us to himself.

The identity of one of these arms, for whom the peoples wait expectantly

in Isa. 51:5, is made clear in Isaiah 53:1: And to whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed?

This is the beginning of the famous Suffering Servant chapter, that talks about Jesus in such clear language, it is forbidden to be read in the synagogue as part of the annual cycle of Scripture reading: He was pierced for our transgressions…. Like a lamb that is led to slaughter…. He will bear their punishments….

(Isa. 53:5,7,11).

It can only be called divine justice that this same one who himself experienced such injustice will come to judge all mankind. When that day comes, Jesus warned, the doors of mercy will be shut (Matt. 25:10-12). But until then, they are open wide for all who would come to the everlasting arms (Deut. 33:27). We will all stand one day before the Messiah for judgment. But if we anticipate his coming, and welcome now the cleansing of the Word and the healing of the Spirit (Matt. 3:11; Eph. 5:26), we can wait in confidence for the day of his return.