David and Bathsheba

David’s Great Sin

by Jeffrey J. Harrison

David’s great sin is set at the turn [the beginning] of the year, when the kings go out for war

(2 Sam. 11:1). For Israel, as for much of the world until recent centuries, the year was considered to begin in the spring.* In Israel, this was the time of fragrant, blossoming flowers and ripening grain, when the cool winter growing season had passed (Song 2:11-13). Military campaigns required firm footing for the troops, which only became available when the sun dried up the winter muds. A raid before the springtime harvest meant that crops standing in the fields could be seized and eaten by an invading army, an act of war that would weaken the defending population.

* In Israel, this was the springtime month of Aviv (the first month of the year, later known as Nissan), which falls in March or April. Only later did Judaism change its calendar to celebrate the new year in the fall, as it is today, at the Feast of Trumpets (today’s Rosh Hashanah).

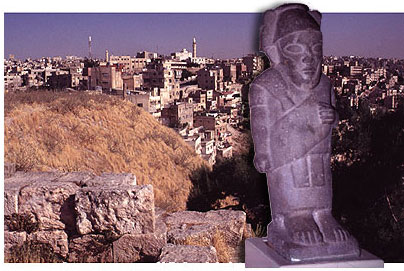

This year, David’s army went out against the Ammonites, descendants of Lot, the nephew of Abraham (Gen. 19:38). The Ammonites lived east of Israel, in the territory of the modern nation of Jordan, around their capital city, Rabbah (Rabbat-Ammon, the great city of the Ammonites

).* The Ammonites were idol-worshippers, whose god Molech (also known as Milcom) had a taste for human blood, specifically the blood of children. This Biblical claim has been proven by the discovery of an ancient worship site near the Amman airport, with evidence of child sacrifice (Lev. 20:2-4, 1 Kings 11:7).

* The remains of ancient Rabbah can be seen in the archeological tell or hill in the center of downtown Amman, the capital of modern Jordan. The modern city preserves the ancient tribal name: Ammon (Amman). It is located just 38 miles from Jerusalem, up in the hill country east of the Jordan River.

David’s war with the Ammonites started the year before, when their new king, Hanun, insulted David’s ambassadors by shaving off part of their beards, and cutting off their tunics at the hips (2 Sam. 10:4-5). David responded with an invasion to the gates of Rabbah. Here, before the city walls, Israel faced the Ammonite army together with 30,000 mercenaries from the Aramean kingdoms in the Golan and modern Lebanon (2 Sam. 10:6-13). But Israel’s victory didn’t end the fighting. It led instead to an even greater clash at Helam, east of the Sea of Galilee, where Israel faced the main forces of all these kingdoms. David and his army were again victorious, and the Aramean kingdoms were subdued (2 Sam. 10:15-19). With this unexpected victory, David was suddenly the most powerful king in the region.

Now, in the following year, David’s troops had returned to beseige Rabbah in hopes of taking the city itself. But David, in an unusual break with his standard procedure, was not with the army. He remained behind in his palace in Jerusalem (2 Sam. 11:1). His absence from what now seemed a minor campaign may reflect his new sense of status as a regional overlord. His victories had extended his reign as far as the Euphrates River in the north, over most of what is today Israel and Lebanon, as well as parts of Syria and Jordan. This was a heady time for the humble shepherd boy from Bethlehem.

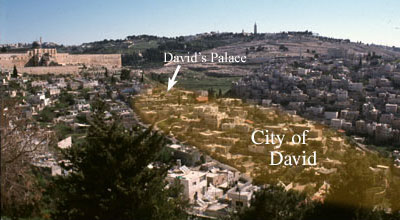

On rising from an afternoon siesta, David took a stroll out on the palace roof (2 Sam. 11:2).* From here, he had a commanding view over his capital city, which he had earlier wrested from the Jebusites (2 Sam. 5:6-9).** The fragrant spring air and golden sunlight provided an intoxicating setting. His new-found glory had every opportunity to eclipse his former humble devotion to God.

* The hours from 1 to 4 in the afternoon are an ideal time for a nap in Israel. Many businesses used to close because of the heat. Roofs, which often served as an outdoor living room, were flat, and had a low wall built around them for safety (Deut. 22:8).

** David’s Jerusalem occupied the hill known today as the City of David, which slopes down to the south of the Temple Mount (see photo above). The palace probably sat above the stepped structure

discovered by archeologists on the top northeast corner of this hill.

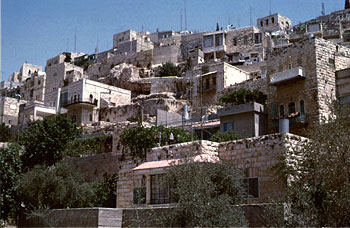

David’s palace sat atop the spine of the hill on which Jerusalem was built. From there, houses descended steeply down the hill’s flanks on either side. The house above often had its entrance at the level of the roof of the house below, and so on down the hill. This meant that from the roof of the palace, David could see the roofs of most of the houses of the city, including one on which he saw a beautiful woman bathing: Bathsheba.

David’s ability to discern Bathsheba’s beauty (and she was very beautiful in appearance,

2 Sam. 11:2) tells us that she was not so terribly far away. Since her husband, Uriah the Hittite, was among David’s top warriors (one of the Thirty,

2 Sam. 23:24,39), this likely meant his residence was up near the palace. If so, the line of sight from her bath would have led, as she must certainly have known, to only one rooftop above.

When David sent for her, there’s no indication that she objected, which also suggests that she was a willing participant (2 Sam. 11:3-4). His lying with her constituted adultery, which bore the penalty of death both for the man and the woman involved (Deut. 22:22). This was a deliberate and willful sin, a sin of the uplifted hand,

for which no sacrifice could be offered in the Tabernacle (Num. 15:30).

Bathsheba remained in David’s palace until she purified herself from her ritual uncleanness

(2 Sam. 11:4). This would be at sunset the next day, after the one-day uncleanness resulting from sexual union had passed (Lev. 15:18).* How strange that she should be so careful to obey this minor precept of the Law, just after violating one of its greater commandments (Exo. 20:14)! Jesus noted a similar impropriety in the Pharisees, whom he rebuked for diligence in minor matters of the Law, while neglecting its more weighty provisions (Matt. 23:23).

* The uncleanness resulting from marital relations was remedied by bathing in water (later interpreted as immersion in a mikveh bath) and remaining impure until evening (Lev. 15:18). This translation fits the Hebrew and the flow of the sentence better than the common alternate reading, for she was cleansed from her impurity,

implying that David only lay with her because her menstrual impurity had passed.

When Bathsheba discovered she was pregnant, David devised a plan to hide their sin (2 Sam. 11:5). He sent for Uriah, her husband, who was at the seige of Rabbah, so it would appear that Uriah had fathered the baby (2 Sam. 11:6-8). But after reporting to David, Uriah faithfully slept at the gate of the palace rather than return home (2 Sam. 11:9). Why did you not go down to your house?

a distraught David asked the next morning (2 Sam. 11:10). Uriah’s reply? The Ark [of the Covenant] and [the armies of] Israel and Judah are staying in temporary shelters, and my lord Joab [the general in charge] and the servants of my lord are camping in the open field. Will I then go to my house to eat and to drink and to lie with my wife?

(2 Sam. 11:11).

Uriah’s devotion to God and to Israel is in dramatic contrast to David’s actions. Uriah wouldn’t take even a small comfort for himself while Israel was at war. This is all the more remarkable considering that Uriah was not an Israelite, but a Hittite, a descendant of one of the Canaanite peoples that lived in the land before the conquest of Joshua (Gen. 15:20, 2 Sam. 11:3). Despite this pagan ancestry, Uriah himself, or perhaps his family before him, had joined the worship of the God of Israel: his name, in Hebrew, means Yhwh is my light.

* Uriah, the foreigner, acts with perfect faithfulness to God, while David, the native king of Israel, is grossly unfaithful.

* Yhwh is the personal name of God, sometimes vocalized Yahweh

or as Jehovah.

The original pronunciation is uncertain. (For more on this topic, see our question and answer category: Yahweh.)

For two more days, David tried to get Uriah to return home (2 Sam. 11:12-13). But Uriah remained steadfast in his commitment to God and to Israel. So David came up with another, more destructive plan. The next morning, he sent Uriah to the battlefield with a letter in his hand: instructions to Joab that he be put in the front lines to be killed in the fighting (2 Sam. 11:14-16).

The camp of Israel to which Uriah returned was likely situated on one of the hills that tightly circled the Ammonite capital.* An elevated location for the Israelite camp not only protected the Israelite army should the enemy decide to venture outside the city walls, but also provided a strategic view for coordinating military movements. The city of Rabbah itself, in the middle of the valley, was built on a lower, though still impressive hill, thanks to its steep sides and huge stone wall. From the top of the wall, the Ammonite defenders shot down arrows or threw down rocks at any Israelite that got too close. Against such a well-defended city, only a long seige could bring victory—unless somehow the defenders could be enticed to come outside the city walls.

* This was standard military procedure, as followed by the Assyrians in their seige of Lachish, and the Romans in their seige of Jerusalem (2 Kings 18:14).

The battle after Uriah’s return is described three times in the verses that follow (2 Sam. 11:16-17,20-21,23-24). If we harmonize these accounts, it seems that the Ammonites made a sudden charge out of the city gate, pushing back the Israelite line. But the Israelites soon regathered their forces and pressed the Ammonites back to the gate. This put the Israelite front line in range of the bowmen on the wall, who shot and killed some of them, including Uriah. David’s plan had succeeded in destroying an innocent man.

You may wonder how David could live with himself, knowing the horrible crimes he had committed, crimes that in God’s eyes were worthy of death. But that’s the question, isn’t it? How are we so good at covering up our sin? As it says in Proverbs, Every man’s way is right in his own eyes...

The Lord, on the other hand, weighs the heart

(Prov. 21:2). And what does he find? As Paul put it, For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God

(Rom. 3:23). A godly person recognizes his failings, and openly confesses and admits his sin before God. But the natural man resists admitting or even recognizing that his actions are sinful (1 John 1:8-10). Thank God that in his mercy, he often intervenes to reveal our sin, that we might repent and be delivered.

For David, God gave an opportunity to repent through Nathan the prophet. Nathan got the king’s attention by telling of a wealthy man who took his poor neighbor’s only sheep for a meal, rather than one from his own large flocks (2 Sam 12:1-4). The parallel with David was intentional: while Uriah had only one wife, David had many (2 Sam. 5:13). David was quick to recognize the sin of the rich man. He declared him worthy of death, and decreed a fourfold restitution for the lamb he had taken (2 Sam. 12:5-6). He even identified the man’s heart problem: he had no compassion,

which was in fact the problem of David’s own heart (2 Sam. 12:6).

The four-fold restitution that David called for is precisely the penalty in the Law of Moses for the theft of a sheep (Exo. 22:1). Clearly, David knew the Law of God; he knew right from wrong. But though he was willing to impose the Law on another, he was not willing to apply it to himself.

That’s when Nathan revealed his hidden message. You are the man!

(2 Sam. 12:7-9). David had been given incredible blessings by God: blessings far beyond what most men could even dream. But for these blessings, David had returned evil. As a result, David would be punished for his evil deeds.

From Nathan’s prophecy of judgment, we can learn something of the nature of God’s justice: David had had a man killed, therefore the sword would never leave his own family (2 Sam. 12:10). He had violated another man’s wife, therefore his own wives would be taken from him and violated in broad daylight (2 Sam. 12:11-12).* The very areas in which he had sinned were those in which he would be punished.

* This actually took place in the rebellion of Absalom several years later (2 Sam. 16:22).

Only then, after hearing the punishments decreed against him, did David repent: I have sinned against the Lord

(2 Sam. 12:13). In this simple confession was an admission to sins worthy of death. But the prophet immediately spoke again, pronouncing the forgiveness of the Lord. The Hebrew says literally, The Lord has caused your sin to pass over; you will not die

(2 Sam. 12:13). Like the angel of death that passed over the Israelites in Egypt, David is spared destruction. The forgiveness of David, himself a symbol of the Messianic king, foreshadows the forgiveness brought by Messiah Jesus: a pardon for sins and rescue from the destruction of eternal death.

David finally faced and admitted his sin. He turned from being a sinner, hiding and covering his sins, to being a man of God, confessing and repenting of his sins—sins to which he never again returned.

But there was one additional consequence for David’s actions: Since you have caused the enemies of the Lord to greatly despise him because of this matter, the son born to you will also surely die

(2 Sam. 12:14). David had given the enemies of God a reason to reject God, a sad reality repeated every time God’s people sin. But God cannot let it appear that sin is acceptable to him. Therefore, David’s son born to Bathsheba would die.

To some, this is a very difficult passage. How could God let this innocent son of David die for David’s sin? But this, too, points to the ministry of Messiah, the greater Son of David,

who died for the sin of the world. The suffering of the innocent for the guilty is the basis of the entire sacrificial system of Israel and its perfect fulfillment in Jesus. There is a price to pay for sin. Jesus, the Son of David,

himself innocent of sin, had to die to pay that price.

All this is wonderful at the symbolic level. But what about this particular child? Why did it have to suffer? This same question can be asked of the millions upon millions of innocents, including many Christians, that have suffered over the years. Why does God allow the innocent to suffer, and the wicked to prosper? David himself recorded God’s answer long ago: Do not get angry because of evildoers...for they will wither quickly like the grass.... Evildoers will be cut off, but those who wait for the Lord.... will delight themselves in abundant prosperity.... and their inheritance will be forever

(Psa. 37:1-2,9,11,18). As in many other places in the Psalms, the answer points beyond this life to reward in the next. The suffering of the innocent is a testimony against the wickedness of this present world, and reason for the coming punishment of the wicked (2 Thess. 1:6). But believers who suffer in godly innocence risk nothing from death. They will be raised even as Jesus himself was, to inherit the kingdom of God.

But what about the ungodly

or unbelieving innocents, in other words, those like this child, or aborted babies, or other infants who die before they have an opportunity to hear and understand the gospel? What will happen to them? The Bible provides no direct answer, only indirect guidelines. On the one hand, we must avoid the simplistic equation of innocence and sinlessness. Though they are innocent of any crime meriting the cruel death they have received, at the same time the Bible says that all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God

(Rom. 3:23). There is none righteous, not even one

(Rom. 3:10). All our righteous deeds are as a filthy garment

(Isa. 64:6). In God’s sight, all of humanity is worthy of death, and none deserves the right

of salvation.

But on the other hand, sinfulness need not be a barrier to God’s mercy. This is the good news in Messiah Jesus: that though all have sinned, God made a way of salvation in Messiah. Though the usual way to receive this forgiveness is to hear and accept the gospel from a fellow human being, there are hints in the Bible that God does not always do it this way. The best example is the saints of the Old Testament. Jesus clearly taught that Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and all the prophets

are among the redeemed (Luke 13:28, Matt. 8:11). Yet they did not hear the gospel in the way that we do today. Their salvation resulted from direct interaction with and faith in the Son of God manifested to them (as in Genesis 18 for Abraham), or the Spirit of Messiah

operating in them (1 Pet. 1:11). David himself received forgiveness for sins for which only the Law of Messiah, and not the Law of Moses, offers forgiveness (Acts 13:38).

There are also rare testimonies of people today being saved through a vision of Jesus, even in non-Christian societies. Might God also do the same for some of these children? Though God chooses to use the church in extending salvation to the nations, ultimately the work of salvation is under his sovereign control. The sower sows the seed, but only God can lead a soul to salvation.

The bottom line is that we don’t know what will happen, and must leave these infants completely in God’s hands. He is the righteous judge, not we. And he will have mercy on whom he has mercy, and compassion on whom he has compassion (Exo. 33:19, Rom. 9:15), not because of any works that we have done, but because of him who calls (Rom. 9:11-17).