THE JEWISH ROOTS OF CHRISTIANITY

Copyright © 2018, 2020 by Jeffrey J. Harrison. All rights reserved.

Cover art, photos, diagrams, and artwork are by the author or are in the public domain. Bible verses translated by the author

For more information on Landmarks of Faith Seminars, contact:

Jeff Harrison

To The Ends Of The Earth Ministries

Jeff@totheends.com

Table of Contents

Preface xiIntroduction 1

Part I. The Fertile Root:

Jews and Gentiles in the Body of Messiah 1

Jewish Christianity 1

Why Should We Care? 2

Pentecost: Something Completely New? 5

Zealots for the Law 6

The Prophet Like Moses 8

Paul and the Jewish Law 8

Gentiles and the Jewish Law 11

The Council of Jerusalem 14

The Three Exceptions 16

Judaizing and Gentilizing 17

Circumcision and Uncircumcision 19

War with Rome 21

Jesus’ Prophecy of Destruction 23

Judaism after the War 25

Jewish Believers after the War 26

Interactions with the Rabbis 27

The Bar Kochba Revolt 28

Debates with the Rabbis 29

Rejection of the Nazarenes 31

The Gospel of the Hebrews 35

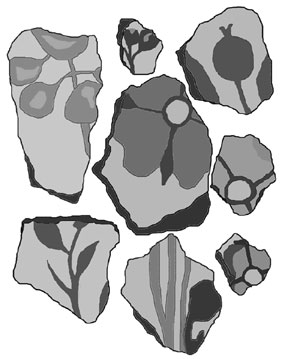

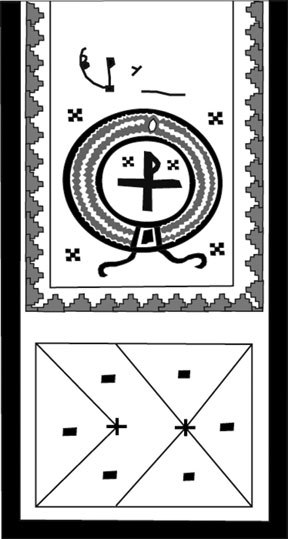

Nazarene Art and Symbols 36

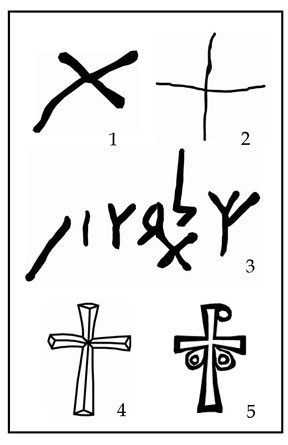

The Cross Symbol 37

Baptism 40

The Angel of the Lord 42

The Book of Revelation 45

Conclusion 46

Part II. Wild Branches:

The Gentilization of Christianity 51

Rome’s Attitude toward the Jews 57

Roman Attitudes toward Christians 60

The Persecution by Nero 62

Winds of War 64

The Epistle of Barnabbas 68

Hadrian versus Jews and Christians 69

The Apologists 71

The Sibylline Oracles 76

Anti-Judaism in Prophecy 78

The Sabbath 80

Passover (Pascha) 86

Marcion 91

Gnosticism and Middle Platonism 92

The Beatific Vision 97

Priestly Celibacy 99

The Saints 102

Worship Services 104

Angels and Idols 106

Church Leadership 107

Conclusion 108

Part III. Uprooting the Tree:

Constantine, the Crusades, and Other Anti-Judaisms 109

The Conversion of Constantine 113

The Emperor as Head of the Christian Church 114

Changed Attitudes toward the Emperor 116

The Intolerance of the Imperial Church 119

The Imperial Church in Prophecy 122

Doctrinal Debates and Church Splits 124

Greek Philosophy and the Jewish God 128

The Rise of the Papacy 133

Continuing Persecution of the Jews 137

The Persian Invasion 138

Early Muslim History and Growth 144

Jews and Christians under Muslim Rule 145

The Impact of Islam on the West 146

The Approach of the Year 1000 152

The Millennium Reinterpreted 153

A Perfect Christian Society 155

The Crusades 157

The Crusading Spirit in Europe 161

The Ritual Murder Charge 163

Host Desecration 164

The Black Death 165

The Inquisition 166

The Ghetto 168

Book Burning 168

Papal Troubles 169

Lollards and Hussites 170

Luther and the Jews 173

The Counter-Reformation 175

The Puritans 175

Separation of Church and State 177

Russia and Poland 177

Communism 179

Germany’s Racial Anti-Semitism 179

The Holocaust 182

Part IV. Beauty Like the Olive:

Christianity and the Modern State of Israel 185

Zionism 191

The United Nations Vote 193

The War of Independence 194

The Six-Day War 195

The Yom Kippur War 197

The Return of the Jewish People in Prophecy 198

Christians Helping Jews Return 200

The Restoration of the Land in Prophecy 201

The Rebirth of Jewish Christianity 203

Attitudes in Israel toward Messianic Jews and Christianity 204

Replacement Theology 211

Old Law and New 212

The Remnant of Israel 216

Invalid Attempts at Restoration 217

Valid Attempts at Restoration 220

Overcoming Christian Imperialism 221

Conclusion 223

Appendix I. Nazarene Influence outside the Roman Empire 227

The Church of the East 227

First Christians in Asia 228

Edessa 230

Parthia (Iraq/Iran) 230

Evidence of Nazarene Influence 231

Pascha 234

Baptism 235

Marriage 235

The Church in India 236

The Church in Arabia 237

Ethiopian Christianity 239

Appendix II. Gentiles in the Law of Moses 242

Appendix III. Abbreviations 248

Preface

That Christianity has Jewish roots is still an uncomfortable thought for many people. To accept it requires a major change in thinking. But though Christianity’s Jewish origins are now widely recognized, the impact of this change has only just begun.

Perhaps you’ve encountered Christianity’s Jewish roots through a Christian Passover meal or a Feast of Tabernacles celebration. Or maybe you have Messianic Jewish friends. You might have gone on a tour to Israel. Or maybe you like Messianic Jewish-style music or dance. You may have noticed the Messianic Jewish synagogues popping up in many places, or the new Jewish studies classes being offered at Bible colleges and seminaries. All these are only the beginning of what is quickly becoming the most important move of God in the Church for many generations: the restoration of the Jewish roots of Christianity.

But the fact that Christianity has Jewish roots raises many questions. What are these roots exactly? And why were they forgotten for so long? What effect is the rediscovery of these roots having on Christians today? And how should we respond to the many different opinions people have about this topic, strong opinions that often contradict one another? You may have heard people claiming that Gentile Christians should obey the Law of Moses: that they shouldn’t eat pork or shellfish, for example, or that they should worship on Saturday. But others, including most Messianic Jewish leaders in Israel, say that this is not necessary for Gentiles. How do we respond to these claims and counter-claims?

To find the answer, we need to dig back into Christian history, especially early Christian history, to find out what the Church’s original teaching on this subject was. That’s what this book is about: discovering the original Christian attitude toward the Jewish roots of the Christian faith, and then finding out what happened over the years when so many of those roots were cut off and left behind. Then, with this background, we’ll be ready to correctly understand what God is doing today in restoring the Jewish roots of the Christian Church.

This teaching on the Jewish roots of Christianity began as a Landmarks of Faith Bible seminar presented to thousands of students and in scores of churches and Bible colleges in the U.S., Taiwan, and the Philippines. It grew out of Pastor Harrison’s experience living in Israel, his classes with some of the top Israeli archeologists and other leading scholars in Jerusalem, and his experience as a study tour teacher in Israel, introducing groups of Christians to the depth and breadth of the history of Israel. He also has a traditional seminary training and has taught the Bible and the history of the Church for more than twenty-five years.

For more information about Pastor Harrison and his ministry, visit his To the Ends of the Earth Ministries website at www.totheends.com.

This

is an excerpt from The Jewish Roots of Christianity by Jeffrey J. Harrison. Available from Amazon.com in print and on Kindle!

For more great Christian books, visit our online bookstore.

For more great teaching visit our website at www.totheends.com

Introduction

Christianity is Jewish? Until recently, this idea was shocking and upsetting to many people. Why was this a problem? Because for most of its history, Christianity defined itself in opposition to the Jews and Judaism. Christians led the way in persecuting Jews, over and over again through the centuries, including the most recent and most horrible persecution of all, the Holocaust that took place during World War II.

The horrors of the Holocaust finally opened the eyes of Christians, for the first time in centuries, to the injustice of this ancient hatred of the Jews and Judaism. Many began to realize how wrong the Church had been in its teaching and in its actions towards the Jews. But this was not just a problem in the Church’s relationship to the Jewish people. It was also a problem in how the Church understood its own identity and some of its most basic ideas: ideas that originated in Jewish culture and Jewish religion.

The rediscovery of the Church’s Jewish roots raises many questions. Why do Christians know so little about their Jewish origins? How did Christianity, which started out as a Jewish religion, become a mostly Gentile religion with great hostility toward the Jewish people? How did this Gentile influence change Christians’ understanding of their own faith? And what is the right way, the correct Biblical way, to get back in touch with our Jewish roots today?

This book is intended to answer those questions. We’re going to examine how Christianity rejected the Jewish people, how this rejection led it far from God’s plan and purpose, and how God is now pointing the way home. But this will not be the kind of Church history most of us are familiar with. There is a dark side to Christian history that most Christians know almost nothing about: a history of hatred, persecution, and rejection not only of the Jewish people in general, but also of Jewish believers in Jesus and others that tried to preserve Christianity’s Jewish roots. This is a difficult history that every Christian needs to know. And God has chosen our generation to hear this message and to act on it.

Some parts of this teaching will be challenging. But each part is important to get the whole picture. So I encourage you to hang in there through the whole teaching: it will be worth it in the end. This information has changed my life, and I believe it will change yours, too, and bring you into a deeper understanding of the Christian faith. Are you ready?

This book is divided into four parts:

1) Early Jewish and Gentile Christianity: What did the church look like when it was still in touch with its Jewish roots? What was God’s original plan for the relationship of Jews and Gentiles in the body of Messiah? There’s a lot of confusion on this topic that we’re going to clear up with the help of some long-forgotten truths.

2) The Gentilization of the Christian Faith: What happened when Christianity came to Rome and to other Gentile cities and towns? How did Gentile Christians understand and how did they misunderstand the gospel? How did a series of horrible wars make bitter enemies of Jews and Gentiles, and bring anti-Jewish attitudes into the Church—along with many misunderstandings of our Jewish and Biblical heritage. Some of these misunderstandings continue today. What are they and how can we correct them?

3) Imperial Christianity: In the 4th century, Christianity went from being the faith of a persecuted minority to the official religion of the Roman Empire. This was the origin of the state church, an official, government sponsored church. State churches can still be found in a few places in Europe today. In a state church, pastors are government employees whose salaries are paid by the government. But this also means they can be controlled by the government. This state church officially cut itself off from its Jewish roots, becoming a Gentile-only religion. The empire also introduced anti-Jewish laws and persecuted Bible-believing Christians that disagreed with its teachings.

Some of the worst atrocities came in the time of the Crusades, church-sponsored invasions in which thousands of Jews, Muslims, and Christians were killed in attacks and battles. Perhaps you’ve heard of the Inquisition: church-sponsored examination and torture of those who disagreed with official church teachings. Many of those tortured were Jewish. There were also other attacks against Jews, including pogroms and expulsions in Western as well as Eastern Europe. These are the pages of history that, as one scholar put it, the Church has torn out of its history books, but which the Jewish people and others have never forgotten—and which we, too, should never forget.

The peak of persecution came not in the Middle Ages, but in the 20th century. The Holocaust was one of the most horrible events in human history, in which six million Jews were killed, along with an equal number of Christian civilians, including many Polish people, Ukrainians, and others. This took place in historically Christian areas: Germany, Russia, and Poland. Many of those who committed these murders were baptized, church-going Christians. How could this happen? The Holocaust was not just a horrible “accident” along the road of history. It was the direct result of a long heritage of hatred and persecution of Jews and others by Christians, a sickness that gripped Christianity for more than a thousand years—and still does today in some places.

4) Christianity and the Modern State of Israel: We’ll also look at the dramatic rebirth of the State of Israel, the most important fulfillment of prophecy since the time of Jesus. More prophecies are being fulfilled in Israel today than at any other time since the life of Jesus. An important part of these prophecies is the rebirth of Jewish Christianity, or as it’s known today, Messianic Judaism. These events came as a shock to many Christians and Christian denominations. What do these amazing prophetic events mean? How does God want us to respond to them? How is God using Israel to restore the Church to its Jewish roots? And what will this mean for the Church in the years to come?

So that’s the plan. If you’d like, please feel free to join me in a word of prayer as we start our studies: Father God, open our hearts and our eyes as we study some of the difficult history of your Church. Help us hear the voice of the Spirit as we consider both the sins and the victories of the past, so that we can grow in wisdom and knowledge, and lead our generation into the truth. In Jesus’ name. Amen.

Part I

The Fertile Root

Jews and Gentiles

in the Body of Messiah

CHAPTER 1:

IN THE BOOK OF ACTS

Jewish Christianity

To many Christians and to many Jewish people, Jewish Christianity, or if you prefer, Christian Judaism or Messianic Judaism, sounds like a contradiction in terms. How can you be Christian and Jewish at the same time? This contradiction can be seen in Christian artwork—even in Israel. The church at the Garden of Gethsemane in Jerusalem has three huge wall mosaics at the front of the church.1 Jesus (Yeshua2) and the disciples appear with light skin, high foreheads, and light-colored hair: they’re shown as Gentile Europeans. But the high priest, Judas, and the others, the bad guys of the story, are shown as Jewish with exaggerated features: dark skin, large noses, and claw-like hands. This is, of course, absurd. Jesus and the disciples were just as Jewish as the others. So why are such inaccurate and insulting pictures allowed in a church, and not only in Israel, but in hundreds of other churches around the world? Why has there been this seeming revulsion to accept Jesus and his disciples as Jewish, and a tendency to paint other Jews as less than human? Why have so many Christians been ignorant of the most obvious truth about our religion: that we worship a Jewish savior, whose Jewish disciples founded a Jewish religion in Israel?

Church of All Nations

1 The Church of All Nations on the Mt. of Olives (1924).

2 Yeshua is the original Hebrew name of Jesus.

Originally, there was only one kind of Christianity: Jewish Christianity. This was the Christianity of Peter, Paul, James, and John. They didn’t stop being Jewish when they accepted Jesus as the Messiah. In fact, you could say they became more Jewish than ever when they accepted Yeshua (Jesus). In their writings, they claim that their belief in Jesus is the fulfillment of what Israel and the Jewish people are all about. It’s why God separated out Abraham from among the peoples. It’s why God spoke to Moses on Mt. Sinai. It’s why God spoke through the prophets: to prepare a people for the coming of the Jewish Messiah. That people was the Jewish people. And the early Jewish believers in Jesus were the first to fulfill this calling when they received him as the Messiah.3

3 These Jewish believers are the we, the first to hope in the Messiah

of Eph. 1:12.

We always tend to focus on the Jewish people that rejected Jesus. But as Paul says in Romans 11, I, too, am an Israelite

(Rom. 11:1). God didn’t reject Paul. Nor did he reject the thousands of other Jews that accepted Yeshua in the book of Acts and in later years. Sure, they were a minority of the population. But God has always worked with a remnant. As Paul put it: Though the number of the sons of Israel be as the sand of the sea, the remnant will be saved

(Rom. 9:27).

Yet this original Jewish Christianity of Jesus, Peter, Paul, James, and John disappeared so completely from history that for centuries it was forgotten. Christians carried on as if there had never been such a thing. Christianity became a completely Gentile religion, cut off from its Jewish roots. Today we must piece together the evidence for the early Jewish Christians like a detective story, sorting out tiny bits and pieces of evidence to find out what happened.

Why Should We Care?

But why should we bother? Why should we care about the early Jewish Christians? As one fellow put it, “Why should I care about such a small group of people that lived so long ago?” What difference does it make to Christianity today, in countries thousands of miles away? Here are five good reasons to start with:

1) Because God himself cares about the Jewish people. The greatest fulfillment of prophecy taking place right now, in our lifetimes, is the restoration of Israel to the Jewish people: the rebirth of the State of Israel. This came as a shock to many Christians and Christian denominations. Why? Because for hundreds of years, Christians had been teaching that God has rejected the Jews and replaced Israel with the Church.4 And yet, miraculously, spectacularly, God has responded to that false teaching with a resounding “No! I have not rejected my people.” In the last generation alone, he has fulfilled dozens of his ancient promises to the Jewish people.5 This is a message from God that we need to listen to.

4 This teaching is known as Replacement Theology. It claims that the church inherited all of Israel’s blessings, leaving the Jewish people with all the curses of the Law.

5 For more on the restoration of Israel, see Part IV, Chapter 1.

2) Because Jesus (Yeshua) is Jewish. The gospels of Matthew and Luke list Jesus’ ancestry generation by generation all the way back to King David—back to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. That’s as Jewish as you can get! Not only did he look like a Jew: he spoke as a Jew, he taught as a Jew, most of his ministry was to his Jewish countrymen. If you remove Jesus’ ministry from this Jewish context, you will misunderstand much of his message and his meaning.6

6 This is the subject of our Jesus of Nazareth Seminar.

3) Because the New Testament is a Jewish book. Nearly all of the New Testament was written by Jewish believers in Jesus, and some of it was written to Jewish believers. One of the first things they teach you when you study Bible interpretation is to find out who is writing, and who they are writing to. Why? It makes a difference. Many churches want to be New Testament churches, but let’s face it, if we really want to have New Testament churches, we have to find out more about our Jewish roots. Otherwise, we will misunderstand what the Bible is talking about.

4) Because Christianity was originally a Jewish religion. As Jesus himself said, Salvation is from the Jews

(John 4:22). Not only were Jesus and his original disciples Jewish, all those thousands saved on the day of Pentecost were, too (Acts 2:41).7 The hundreds saved in the Temple at the preaching of Peter and John were all Jewish (Acts 4:4). In fact, the entire Jesus movement was almost completely Jewish for more than ten years after the resurrection of Jesus.8 That’s how many years it took before they realized the gospel was also for Gentiles!

7 They had come up to Jerusalem from all over the world to celebrate the Jewish feast of Shavuot (also known as Weeks or Pentecost; Acts 2:5).

8 The Samaritans saved in Acts 8 were partly Jewish by ancestry. The Ethiopian Eunuch, who had come to Jerusalem to worship

was likely a convert (a proselyte) to Judaism (Acts 8:27). Only when Peter preached at the house of Cornelius did the gospel start to go out to the Gentiles (Acts 10). Even then, many of the Jewish believers had misgivings about preaching to Gentiles, a problem not finally resolved until the Council of Acts 15 in AD 49 (Acts 11:2-3).

In the early years, Jesus’ Jewish believers only preached the gospel to Jews, ...telling the word to no one except to Jews alone

(Acts 11:19). This is the way the gospel was first spread, as a purely Jewish message, to Damascus (in Syria), Phoenicia (today’s Lebanon), Antioch (in Turkey), Cyprus, Alexandria (in Egypt),9 and Cyrene (in Libya), all as recorded in the book of Acts (Acts 9:2; 11:19,20; 18:24,25); but also, as we know from history, to Rome,10 and as far as India in the East11—all before the gospel was preached to the Gentiles! All of the most important ideas of this message—ideas like resurrection, Messiah, and a covenant relationship with God—these were all Jewish ideas, and unfamiliar to Gentiles.12

9 Assuming that Apollos of Alexandria, the Jewish preacher mentioned in Acts 18:24, heard the gospel in his home town. Eusebius says, speaking of the time before AD 49, that “the apostolic men [in Alexandria] were, it appears, of Hebrew origin, and thus still preserved most of the ancient customs in a strictly Jewish manner” (Church History 2.17.2).

10 The expulsion of the Jews from Rome because of a certain “Chrestus” (Christ) is evidence of the spread of the gospel in the Jewish community there before AD 49. This same expulsion is mentioned in Acts 18:2. The book of Romans, too, indicates that Paul was writing to a community that had not yet fully accepted the equality of Jews and Gentiles in Messiah (AD 57). Ambrosiaster, writing in the 4th century, said the Romans “had embraced the faith of Christ [before Paul’s visit], according to the Jewish rite, although they saw no sign of mighty works nor any of the apostles.” In the preface of his Commentary on Romans; in F. F. Bruce, The Spreading Flame (London: Paternoster Press, 1958; reprinted, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982), 136.

11 Archeological evidence supports the penetration of the gospel into India by AD 45. Evidence of the originally Jewish nature of Christianity in India includes eyewitness testimony of a Hebrew copy of Matthew in the 2nd cent. AD. Jewish traditions can still be found in the Indian Christian community today. See Appendix I.

12 Acts 17:32. The once popular theory that many New Testament ideas are foreign to Judaism has been effectively silenced by the Dead Sea Scrolls and other recent discoveries.

The disciples never said when they accepted Jesus (Yeshua) as Messiah that they left one religion and joined another. They never taught that Christianity was a new religion. Instead, they claimed that belief in Jesus is what we might call the “true Judaism,” the correct understanding of what Judaism is all about, and a fulfillment of that same Jewish religion.13

13 Origen in the 2nd cent. AD used the term “perfect Hebrews” to describe Jewish believers in Jesus (On Pascha 2).

5) Because even Gentile Christians are part of what God is doing with Israel. As Paul wrote to Gentile believers in Ephesus: Remember that you were at that time without Messiah, alienated from the citizenship of Israel and strangers to the covenants of promise

(Eph. 2:12). But now, he says, ...you are no longer foreigners and strangers, but you are fellow-citizens with the holy ones and members of the household of God

(Eph. 2:19). The relationship of Gentile Christians to Israel is illustrated in the olive tree of Romans 11. That tree is Israel. Some branches have been broken off, other branches have been grafted in—but it’s still the same tree (Rom. 11:17-24). Israel is the root; Gentile believers are among the branches.14

14 Eusebius calls some faithful Gentile Egyptian Christians who suffered martyrdom in Palestine “inwardly true Jews, and the genuine Israel of God” (Martyrs of Palestine 11.8; early 4th cent.; cf. Rom. 2:29, Gal. 6:16).

Israel, in fact, is the focus and the heartbeat of God’s interaction with mankind—even if nearly the whole nation should turn away from God, as happened in the time of Elijah (1 Kings 19:14,18). Why? Because the true Israel is the spiritual remnant of the nation. As Paul said in Romans 9, quoting Isaiah: Though the number of the sons of Israel be as the sand of the sea, the remnant will be saved

(Rom. 9:27, Isa. 10:22). And because of that holy remnant, Israel was and still is the apple of God’s eye (Deut. 32:10). The good news is that we as Gentiles have been invited to join that remnant: that God is willing to accept us, too, into his chosen people.

The coming together into unity of the remnant of Israel and a believing remnant of the Gentiles is one of the reasons Jesus died on the cross. As Paul said in Ephesians: But now, in Messiah Jesus, you who once were far away [believing Gentiles] were made near by the blood of Messiah. For he himself is our peace, who made both [Jews and Gentiles who believe in Jesus] one and destroyed the dividing wall…, the hostility between the two, in his flesh…that in himself he may create out of the two one new man…by means of the cross

(Eph. 2:13-16).

Satan has done everything he can over the years to destroy that unity and tear it apart. But that doesn’t change the fact that it is still God’s plan for Gentile believers in Jesus to be incorporated into the spiritual reality of Israel. We, too, have become citizens of the Jewish kingdom of a Jewish king: King Jesus (King Yeshua), who rules and reigns over his Messianic kingdom.

Pentecost: Something Completely New?

This is not the traditional Christian view. Many Christians see the day of Pentecost in Acts 2 as the start of something completely new, the new religion of Christianity. It’s often called the “birthday” of the Church, as if it was totally disconnected from all the preceding history of Israel. But that’s not how the disciples themselves understood it. Peter quoted the prophet Joel that day to explain what was happening, saying: And it will be in the last days, says God, I will pour out of my Spirit on all flesh

(Acts 2:17 quoting Joel 2:28). The Messiah was to come at the end of time, at the completion of the age.

As the apostle Paul put it, When the fullness of time came, God sent his Son

(Gal. 4:4). This fullness of time

is imagery from the water clocks used in Roman times. When the container filled with water, it was the end of the time marked on the container. The Messiah, in other words, came at the end of the age, in the fullness of time. For the disciples, this was not the beginning of the story, but the last chapter in a story that was already ages old, tracing all the way back to Moses and Abraham, even back to Adam himself.

The festival this happened at, the festival of Pentecost, is one of the Biblical feasts the Jewish people celebrate every year, also known as the Feast of Weeks, or in Hebrew, Shavuot (Lev. 23:15-21). In Judaism, Pentecost is the anniversary of the giving of the Law on Mt. Sinai. On this day, they remember their incredible experience in the desert, when a thick cloud descended on Mt. Sinai with thunder and flashes of lightning and the loud blast of a trumpet (Exo. 19:18,19). No wonder God chose this day to send the Holy Spirit on the apostles, with the noise of a strong, rushing wind, and with tongues of fire resting on each one of them (Acts 2:2,3). God was descending again in the fire of the Holy Spirit!

As at Sinai, this was a revelation from heaven to change something in their relationship with God. As Jesus said just a few days before, You will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you, and you will be my witnesses

(Acts 1:8). The Jewish people had long recognized obedience to God’s Word—to his Law—to be a witness to the nations. Even the tablets of the Ten Commandments are called the tablets of witness

(Exo. 31:18). They were a witness to the reality of God’s covenant with his people. But now that testimony would no longer be engraved on tablets of stone, but on the hearts of men.

As Jeremiah prophesied: I will put my Law in their inward parts, and on their heart I will write it

(Jer. 31:33). This is what in the New Testament is called the Law of the Messiah (1 Cor. 9:21, Gal. 6:2), the law of faith (Rom. 3:27), the law of liberty (James 1:25, 2:12), the Royal Law (James 2:8), the commandment of the Lord (2 Pet. 3:2), the holy commandment (2 Pet. 2:21), the commandment (1 Tim. 6:14), his commandments (1 John 2:34, 2 John 1:6), or as Jesus said, my commandments (John 14:15,21; 15:10): an inner law of holiness that is in us because of the presence and the power of the Holy Spirit in our lives.

To the Jewish disciples of Jesus, this new Law was not a contradiction of the Law of Moses, but its confirmation. As Paul says in Romans 3, Do we make the Law of no use, then, through faith? May it never be! Rather, we confirm the Law

(Rom. 3:31). In Romans 8, Paul says that the new law of the Spirit was given in order that the requirement of the Law [of Moses] may be fulfilled in us who do not walk according to the flesh, but according to the Spirit

(Rom. 8:4). The Spirit of God in us gives us the power to fulfill the requirements of the Law of Moses!

Zealots for the Law

The book of Acts tells us that the thousands of new Jewish believers in Jesus in Jerusalem were all zealots for the Law

(Acts 21:20). Instead of abandoning the Law of Moses because of their faith in Yeshua, they became more devoted to the Law than they had ever been before! The same thing often happens today. Jewish people who become believers in Jesus often “rediscover” their Jewishness, and suddenly become very interested in Jewish history, Israel, and the Jewish Law.

The obedience of Jewish believers to the Law of Moses has been a big stumbling block for Gentile Christians over the years. When I first heard about it, I couldn’t accept it, because it contradicted traditions I had been taught in church and in seminary. But the facts of the Bible are indisputable, as most scholars recognize today.

Model now at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem

For example, the early Jewish believers in Jesus continued to worship in the Temple in Jerusalem, even after the resurrection and ascension of Jesus:

Luke 24:53 And they were constantly in the Temple, blessing God.

Acts 2:46: Every day…spending a lot of time with one mind in the Temple

Acts 3:1: Peter and John were ascending into the Temple at the ninth hour, the hour of prayer

Acts 3:11: All the people ran together to them in the portico called Solomon’s [located in the outer courts of the Temple]

Acts 5:12: They were all with one mind in the Portico of Solomon

Acts 5:21: They entered about dawn into the Temple and were teaching

Acts 5:42: Every day…in the Temple...they didn’t stop teaching and telling the good news of Jesus the Messiah

They also continued to participate in synagogue worship:

Acts 9:2: He asked for letters to Damascus to the synagogues, so that if he found some who were of the Way [followers of Jesus]

Acts 22:19: From synagogue to synagogue I was imprisoning and beating those who believe in you

James 2:2: For if a man in shining clothes with gold rings on his fingers enters into your synagogue

15

15 This is often translated differently, but the original Greek here is clearly synagogue.

The same root appears in verbal form in Hebrews 10:25: “...not giving up our meeting (episynagogeen) together.”

In fact, the first name used for the Christian movement by believers themselves was not Christianity.16 It was called the Way

(ha-Derekh in Hebrew):17

Acts 9:2: So that if he found some who were of the Way

Acts 19:9: But as some were becoming hardened...speaking evil of the Way

Acts 19:23: A commotion took place, and not a little one, concerning the Way

Acts 22:4: Who persecuted this Way to the death

Acts 24:14: According to the Way that they call a sect

Acts 24:22: Felix, since he understood the facts concerning the Way more accurately

2 Peter 2:2: The Way of the truth will be slandered

16 The name “Christian,” which is a Greek translation of the Hebrew term “Messianic” (Meshichi), was first used of the church in Antioch more than ten years after the Day of Pentecost (Acts 11:26). In Israel, outsiders called the believers Nazarenes, the name still used in Israel for Christians today (Notzrim).

17 This same Hebrew word is used in the Old Testament to describe a life of obedience to the revealed commands of God: the way of the Lord,

the way of peace,

the right way

(Gen. 18:19, 24:48; Jud. 2:22; Psa. 27:11, 77:13, 86:11, 139:24; Pro. 10:29; Is. 40:3, 59:8; and many others).

Belief in Jesus was seen as the “way” to go, the way to live, or we could say, rules for living.18 It was not so much a creed of correct beliefs, although beliefs were certainly important. But the emphasis was on how you lived. This is still the focus of Judaism today. Rabbis teach their students the correct way to live, the correct way to obey the Law of Moses (the halakha19). In the same way, Jewish believers understood that their rabbi, Yeshua (Jesus), had given them the correct Way to live, the correct interpretation of the Law of Moses.

18 This self-understanding can be seen in the Didache, an early writing of the “Way” thought to have been composed in Syria in the first or second centuries AD. It presents the Christian faith as a choice between two ways: one was the Way of life taught by Jesus, the other was the way of death.

19 This means literally “the walk” or “the way to walk (or live)” in obedience to the Jewish Law.

The Prophet Like Moses

This was one of the Jewish expectations of the Messiah: that the Messiah would resolve all the difficulties of the Law of Moses. Where did they get this idea from? From Deut. 18:18,19, one of the most well-known prophecies about the Messiah: I will raise up a prophet for them from among their brothers like you [Moses], and I will put my words in his mouth, and he will speak to them all that I command him.... The man that will not listen to my words that he will speak in my name, I will require it from him.

This was a prophecy that God would send a prophet “like Moses,” that is, not an ordinary prophet, but one with the law-making authority of Moses himself to explain God’s Law. And how would they recognize this prophet? God said he would “raise him up” (Deut. 18:18). In Hebrew, this is the same word used for resurrection (Hos. 6:2, Jer. 30:9).

That’s why when Jesus asked the disciples, Who do men say that I am?

(Matt. 16:13), they answered, John the Baptist, or Elijah, or one of the other prophets: all people that were already dead. Because of Deut. 18:18, they were looking for a prophet who had been raised from the dead. But it wasn’t until after the resurrection of Jesus that they understood its true meaning: It was a prophecy of Jesus’ own resurrection, and the proof that he is the Prophet like Moses, who interprets God’s Law for us, and whose words must be obeyed.

For the early Jewish followers of the Way, it would be impossible to imagine any contradiction between the Law of Moses and the Law of Messiah. Christianity was not a replacement of Judaism, but its fulfillment. As Jesus himself said, Do not suppose that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I did not come to abolish, but to fill them

(Matt. 5:17).20 So of course his Jewish followers continued to live as Jesus himself did, obeying the Law of God as Jesus had interpreted it for them.

20 ‘The Law and the Prophets’ is the Jewish name of the Old Testament. The word fill

(plerosai) here means not only to fulfill as in fulfilling a prophecy, but also to fill with their proper meaning, to interpret correctly, as Jesus did both in his life and his teaching ministry. Unfortunately, many Christians have taken this verse to mean that Jesus fulfilled and therefore did away with the Law and the Prophets, even though this directly contradicts the first part of the verse, as well as the verse following: For...until the heaven and the earth pass away, a single iota [the smallest letter] or a single stroke will certainly not pass away from the Law until all comes to pass

(Matt. 5:18). See the analysis of New Testament verses in Part IV, Chapter 2.

Paul and the Jewish Law

Many are willing to admit that Jesus himself observed the Jewish Law, along with many of his disciples: those that were zealots for the Law

(Acts 21:20). But what about Paul? Did he obey the Law? There is a popular view that Paul was against the Law of Moses. Some go so far as to claim there was a split between the followers of James in Jerusalem, who kept the Law, and the followers of Paul, who did not. Is this true? Was Paul really against the Jewish Law, as so many believe?

According to the book of Acts, many years after accepting Jesus, Paul took a vow: ...he had shaved his head in Cenchrea, because he had made a vow

(Acts 18:18). What kind of vow was this? A Jewish Nazirite vow, taught in the Law of Moses (Num. 6:1-21).21 Why would Paul do this as a believer in Jesus, if he was against the Law?

21 Samson, Samuel, and John the Baptist were life-long Nazirites, but this was quite unusual. The Nazirite vow was usually of much shorter duration, often for thirty days.

He continued to observe the Jewish feasts, as it says in Acts 20:6: We sailed from Philippi after the days of Unleavened Bread...

Why after the feast? Because the Law forbid travel on holy days. Or as it says in Acts 20:16: ...for he [Paul] was hurrying to be in Jerusalem, if it was possible, on the day of Pentecost.

Why? To celebrate the feast. And again in 1 Cor. 16:8: But I will remain in Ephesus until Pentecost...

Paul continued to follow the Jewish festival calendar.

On another trip to Jerusalem, Paul found out that the rumor had gone out, just as it has gone out today, that he was teaching Jews to stop observing the Law and to stop circumcising their children: They have been informed about you that you are teaching apostasy from Moses to all the Jews among the Gentiles, saying not to circumcise their children or walk according to the customs [of the Jews]

(Acts 21:21). What did he do about it? He went up to the Temple, not only to prove that these charges were false, but also to prove that he himself was faithfully keeping the Law (Acts 21:23-26). As he said later in Acts 25:8: Neither against the Law of the Jews, nor against the Temple...have I committed any sin.

The accusations against Paul were similar to those against Stephen in Acts 6:13-14: And they set up false witnesses saying,

Notice that it was the false witnesses that said Jesus would change the Law!

This man does not stop saying things against the Holy Place [the Temple] and the Law; for we have heard him saying that this Jesus, the Nazarene, will destroy this place and change the customs that Moses delivered to us [the Law].

But perhaps the most powerful argument about Paul is this: If Paul was really against the Law, why did he circumcise Timothy? Paul wanted this man [Timothy] to go with him; and having taken him, he circumcised him because of the Jews who were in those places

(Acts 16:3). But isn’t Paul the one who said to the Galatians: If you become circumcised, Messiah will not benefit you at all

(Gal. 5:2)? What’s going on? Is Paul for or against circumcision? Is he for or against the Law of Moses?

Let’s let him answer this puzzle in his own words: Was anyone called who is circumcised [in other words, who is Jewish22]? Let him not become uncircumcised.23 Was anyone called in uncircumcision [in other words, a Gentile]? Let him not be circumcised....

(1 Cor. 7:18,20).24 According to Paul, being a Jew (circumcised) or being a Gentile (uncircumcised) is a calling of God that cannot and should not be changed when you become a believer in Jesus.

Each in the calling in which he was called,

let him remain in this calling

22 Circumcision in the New Testament does not refer simply to the physical act of circumcision, but rather to the entire ritual of circumcision by which one enters into the covenant of Abraham and becomes responsible to the Law of Moses. This does not include Gentiles circumcised for health reasons.

23 An operation called epispasm could be done to remove the signs of circumcision.

24 Paul uses the saying each in the calling in which he was called

as if it were already familiar to his readers.

Timothy was Jewish because his mother was Jewish. This is what makes someone Jewish even today (Acts 16:1).25 Therefore he should be circumcised. But the Gentile Christians in Galatia should not be, since they are Gentiles. A Gentile should continue as a Gentile; and a Jew should continue as a Jew, which includes obeying the Law of Moses.

25 Although “who is a Jew?” is a hotly debated topic, one definition to which all have agreed since the time of the New Testament is that the children of a Jewish mother are Jewish.

This doesn’t mean that the Law can contribute anything to salvation. It can’t. Nothing is more obvious to a Jewish believer in Jesus that obeyed the Law all his or her life, but was never saved by it (Gal. 2:16). Salvation is only through faith for both Jew and Gentile. This is just as true now as it was in the time of the Old Testament, for salvation was only ever by faith (Gal. 3:11).26 As Paul puts it in Gal. 3:6, Abraham believed God, and it was counted for him as righteousness.

26 This is the whole point of Paul’s argument in Gal. 3: that salvation was never available through the Law (Gal. 3:11). The popular idea that salvation was once available through obedience to the Law is contrary to this clear Biblical teaching.

But for many Gentile Christians, for Jewish Christians to obey the Law doesn’t make sense. If observing the Law is not essential to salvation, and in fact never provided salvation, why should Jewish believers in Jesus obey it? The answer: because God told them to. He made a covenant with them, which the Bible says will endure as long as the heavens and the earth endure (Matt. 5:18). Have the heavens and the earth passed away? No. Then it’s still in force! As Jesus said, Do not suppose that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets

(Matt. 5:17). Obedience to the Law is not and never was a means of salvation (Gal. 2:21).27 But it continues to play an important role: to point to the Messiah, and to confirm that Jesus is who he says he is!

27 As it says in Gal. 3:21: For if a law was given that was able to give life, righteousness would surely have been by law.

Does faith then invalidate the Law? May it never be! Rather [through faith] we confirm the Law

(Rom. 3:31).

As Paul says in Romans 11, speaking about this same point: For the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable

(Rom. 11:29). Jews are Jewish, and as Jews, they should continue to keep the Law of Moses, even after coming to faith in Messiah: it’s their calling.28 Remember, too, that at the time, the Law of Moses was the law of the land.29 It would make no more sense for a Jewish believer in Jesus to break the Law of Moses than for a Gentile Christian to break the laws of his own country. The Bible says that we should obey the authorities over us (Rom. 13:1-7, 1 Pet. 2:12-15). How much more when you know that those laws were given by God himself!

28 Augustine of Hippo (5th cent.) argued that a sudden cancellation of the Law with the coming of Messiah would have given the false impression that the Law, which Paul called “holy and good” was instead “worthy of abhorrence and condemnation.” Letters of Augustine 82.2.15; in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series (NPNF1), ed. Philip Schaff, (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1886; repr. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1995), 1.354. In order to avoid this charge, God ordained the Law to continue among Jewish believers in Jesus. But it was not commanded for Gentiles, in order to show that the Law was not necessary for salvation. Augustine’s words were prophetic: those who believed that the Law had been abruptly cancelled came to exactly this conclusion—that it was “worthy of abhorrence and condemnation”—and abhorred the Jewish people along with it.

29 Both in Israel and elsewhere in the Roman world, Jewish population centers were allowed to regulate themselves according to the Law of Moses, which was officially recognized by the Roman Empire.

Now that is a different point of view than we’re usually taught! And it just might make us downright uncomfortable. When I first heard this idea from modern Messianic Jews, I couldn’t accept it. It went against ancient prejudices I’d been taught in seminary. But as I studied the evidence, verse by verse, in Greek and in Hebrew, I was shocked to find: they’re right! It’s what the Bible has always taught. And it’s what the early Jewish Christians did without debate or disagreement for hundreds of years. We Gentile Christians just forgot how to understand these verses correctly.

Gentiles and the Jewish Law

So if Israel is the focus of God’s work in the world, and we Gentile Christians have been grafted into Israel, what about us? Are we supposed to keep the Law, too? If we are fellow citizens with the holy ones, as Paul says in Ephesians 2:19, shouldn’t we obey the same laws that they do? This was the big question troubling the early Church. They never questioned whether Jews should obey the Law, but what about us, the Gentile Christians? Do we need to observe the Sabbath, as some teach? Do we need to avoid pork, as others teach? What about blood? What about Jewish festivals? Today there are many groups teaching that Gentile Christians must obey the Law of Moses. Are they right?

The place of Gentiles with regard to Jewish religion was not a new problem in the time of the book of Acts: the Jews had already spent hundreds of years debating whether Gentiles should obey the Law of Moses or not. Some rabbis, we’ll call them Group A, taught that Gentiles who wanted to serve God should convert to Judaism: they should become proselytes.30 This meant they had to obey all the Jewish laws, just like those born Jewish.

30 There were three steps to becoming a proselyte: (1) circumcision (for males), (2) ritual immersion, and (3) offering a sacrifice in the Temple in Jerusalem. Nicolas, one of the seven deacons of Acts 6 was a proselyte from Antioch (Acts 6:5).

But other rabbis, we’ll call them Group B, taught that it was not necessary for Gentiles to observe the Law of Moses.31 The Law was a covenant between God and the Jewish people alone.32 Instead, they said, it’s enough for Gentiles to observe a much smaller group of laws that later came to be known as the Laws of Noah.33 Where did they get these laws? Most likely from the sections of the Law of Moses that concern Gentiles living in Israel.34 The Laws of Noah were eventually standardized as seven: “The descendants of Noah were commanded seven precepts: [1] to establish courts of justice, [2] to refrain from blasphemy, [3] idolatry, [4] sexual immorality, [5] murder, [6] robbery, and [7] eating flesh cut from a living animal [that is, with its blood still in it].”35

31 See, for example, the story of Izates, the king of Adiabene in Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews (20.2.3-4). After he became convinced of the truth of the Jewish religion, one Jewish teacher discouraged him from becoming circumcised while another pressed him to do so.

32 bSanh. 59a. This was also the understanding of the earliest Christians: “For the law promulgated on Horeb…belongs to yourselves [the Jewish people] alone.” Justin Martyr, 2nd cent., Dialogue with Trypho 11, Ante-Nicene Fathers (ANF), ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 1.200.

33 The Laws of Noah were formalized after the time of the New Testament. But the idea of seven Noachide laws can already be seen in the book of Jubilees, which dates to the pre-Christian era and was influential in early Christianity (7:20,28,29). The Laws of Noah are mentioned in many places in rabbinic literature, including Gen. Rab. 16:6, 24:5, 34:8; bSanh. 56a-59b; bHul. 92a; and bBK 38a. This body of law was later associated with the “Natural Law” of Gentile Christian theology, as already in Tertullian, 3rd cent., An Answer to the Jews 2.

34 These are the laws concerning the gerim, Gentile strangers who lived among the Israelites (see Appendix II). This body of law closely matches the rabbis’ seven laws: the prohibition of sexual immorality (Lev. 18:26), the prohibition of eating blood (Lev. 17:10,13,15), the prohibition of idolatry (Lev. 20:2), the prohibition of blasphemy (Lev. 24:16), and the prohibition of murder (Lev. 24:22). They also match many of the Ten Commandments. The rabbinic and Christian attempts to derive these laws from the early chapters of Genesis were clearly secondary to the formulation of the laws themselves (Gen. Rab. 16:6, 24:5; Tertullian, An Answer to the Jews 2).

35 bSanh. 56a. Only two of these laws are clearly stated in the Biblical account of the Covenant of Noah: the prohibition of murder (Gen. 9:5,6) and the prohibition of blood (Flesh with its life, its blood, you will not eat

; Gen. 9:4). A third, the establishment of courts, is said to be implied by Gen. 9:6: The one shedding the blood of man, by man his blood will be shed.

Note that the rabbinical list leaves out the command to observe the Sabbath (more on this in Part II).

The rabbis of Group B accepted any Gentile who was willing to obey the Laws of Noah. They called them Godfearers or Fearers of Heaven.36 Modern Judaism uses the terms Righteous Gentiles or Sons of Noah (B’nei Noach). These are the same Godfearers that appear in the book of Acts, where we see them worshiping in synagogues with the Jewish people. Such a Gentile, they taught, will have a share in the world to come. So for the rabbis of Group B, the Gentiles have their own law, the Laws of Noah, and their own accountability before God, which is different than that of the Jewish people. Or to express it another way, Gentiles who want to be perfectly obedient to the Law of Moses need only keep the Laws of Noah, since this is the section of the Law of Moses that applies to Gentiles.37 In later years, this second point of view, the view of Group B, was accepted as the normative view in Judaism, and is still taught today.

36 “Fearer of heaven” (yirei shamayim) was the Hebrew term; “Godfearer” was its Greek equivalent (phoboumenoi ton theon in Acts 10:2,22,35; 13:16,26) as well as “worshipper (of God)” (sebomenoi in Acts 13:50; 16:14; 17:4,17; 18:7).

37 The Laws of Noah are held by the rabbis to be validly observed only if they are accepted as part of the Law of Moses.

This idea of different religious laws for different groups of people is difficult for many modern Gentiles to accept. Our legal and religious systems have, at least in modern times, developed a strong moral tendency toward treating all people alike.38 But in the Law of Moses, there are different laws for men and women, for priests and Levites, for kings, for children, for married, for single—and for Jews and Gentiles. Each has a special calling, and there are different laws that apply to each calling.

38 Though many legal differences remain: children have a different position before the law than adults, as do citizens and non-citizens, landlords and tenants, manufacturers and consumers, employers and employees, spouses and non-spouses, etc.

Take, for example, the case of pork: the Jewish people are forbidden to eat it, while Gentiles are not. This difference in law is disturbing to some people. How can both eating pork and not eating it be acceptable to God? Well, as the rabbis explain it, the prohibition of pork is not intended to imply anything about the pork itself. Pork is a perfectly good food. So why did God prohibit pork for the Jewish people? To set them apart from others—period.39 It’s part of their special calling. This is not because pork is bad for you, or has something about it physically or spiritually that makes it unclean. It’s simply because God, for reasons unknown to man, selected pork to be forbidden to the Jewish people. As Lev. 11:7 says, It is unclean for you

—the Jewish people.40 It doesn’t say anything about it being unclean in itself or to others.

39 This is already the point of view taken in the Letter of Aristeas (2nd cent. BC) 143-144. Many have tried to find physical reasons for the food prohibitions of the Law of Moses, and have come up with many fascinating insights. But the bottom line remains God’s decision to separate the Jewish people.

40 Leviticus 11 is clearly addressed to the sons of Israel

(Lev. 11:2), and not to the Gentiles living among them. Jesus did not reverse this teaching of the Law, despite the common mistranslation of Mark 7:19 as ‘thus he declared all foods clean.’ Here Jesus was disputing the tradition of the Pharisees about eating food with unwashed hands. Nor did Jesus teach against any other precept of the written Law. As he himself said, Do not suppose that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets...

(Matt. 5:17). For more on this controversy, see our teaching “Did Jesus Abolish the Jewish Food Laws?” at https://www.totheends.com/hands.html

This is exactly the point of view of the apostle Paul in Romans 14:14: I know and am convinced in the Lord Jesus that nothing [he’s talking about food] is unclean in itself.

Paul agreed with the rabbis of Group B that observing the Law of Moses is not required for all mankind. If you are a Gentile believer and you stop eating pork, it won’t make you any more holy. Why not? Because the pork itself is not the issue. The issue is whether or not you are being obedient to the calling that God has given you. Circumcision [that is, being a Jew] is nothing, and uncircumcision [being a Gentile] is nothing, but rather keeping the commandments of God

(1 Cor. 7:19). A Jew who obeys God will not eat, because it’s forbidden to him, and a Gentile who obeys God is free to eat. Why? Because each has his own calling from God: Each in the calling in which he was called

(1 Cor. 7:20); for the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable

(Rom. 11:29).

But what about Galatians 3:28?: There is no Jew or Greek, there is no slave or free, there is no male and female, for you all are one in Messiah Jesus.

Doesn’t that prove we are all the same, with no differences between us? Does it? It certainly proves that we are all one body in Messiah. All of us are accepted by faith, no matter what kind of person we are. But does this mean that men stop being men and women stop being women? Of course not. Nor does it mean that Jews stop being Jews or Gentiles stop being Gentiles. We all have our individual callings. But, Paul says, in spite of this diversity of callings, in spite of these differences in personal identity, we are all one in Messiah. Diversity in unity, unity in diversity: this is one of the great truths and the great revelations of the New Testament.

God doesn’t want a gray uniformity, an army of robots with everyone doing exactly the same thing. What he wants is unity, like a symphony orchestra, all working together toward a shared goal. But each plays a different instrument with different notes. This is the same God who made thousands of different flowers, thousands of different trees, yet all blend harmoniously into beautiful landscapes. This is Paul’s vision for the body of Messiah: one body and one Spirit…. But grace was given to each of us individually, according to the measure of Messiah’s gift to each of us…. from whom the whole body…is, as a result of the action corresponding to the measure of the gift given to each individual part, causing the body to grow by building itself up in love

(Eph. 4:4,7,15,16). Paul’s language is a little difficult, but the point is crystal clear: the body of Messiah best matures in love when each of us is operating in harmony with the others, according to our own individual gifts and callings.

The Council of Jerusalem

The Jewish followers of Jesus were at first split on the issue of Gentiles and the Law. Some, influenced by the rabbis of Group A, felt that to be a true follower of the Way, Gentiles must convert to Judaism. Others, influenced by the rabbis of Group B, felt that Gentile believers were not required to convert and keep the Law of Moses. The issue finally came to a head in Antioch when Paul and Barnabas got into a fierce debate with a group of Jewish believers from Judea (Acts 15:1,2; Gal. 2:12-14).

Because of this, the leaders of the Messianic community held a meeting in Jerusalem to decide what to do about the Gentiles.41 The believers who were Pharisees said that Gentile believers must be circumcised, that they must become proselytes (converts) to Judaism (Acts 15:5). Peter, speaking for the other side, told of his experience at Caesarea, when God sent the Holy Spirit on uncircumcised Gentiles, a sign that they should be accepted without circumcision (Acts 15:7-11). Paul and Barnabas told of the signs and wonders God had done for uncircumcised Gentiles during their missions outreach in Turkey and Cyprus (Acts 15:12). Then a decision had to be reached.

41 Acts 15, in AD 49.

That’s when James, the brother of Jesus, began to speak. He quoted a passage from the book of Amos in favor of the position of Peter and Paul: After these things, I will return and rebuild the tent of David that has fallen, and I will rebuild its ruins and restore it, so that the rest of mankind will seek the Lord, and all the Gentiles over whom my name has been named

(Acts 15:16-17, quoting Amos 9:11-12).42 On the basis of this verse, the issue was settled. Why? What does it mean? What is the tent of David?

42 James’ quote of Amos is strongly influenced by the Old Greek translation of the Bible (the Septuagint), which understands the Edom

of Amos 9:12 to be Adam

(mankind). The two are quite similar in Hebrew, not to mention that the rabbis often interpreted Edom as a prophetic reference to the Roman Empire. Few modern translations bring out the full force of the original, literally: for whom my name has been named over them

(though compare the King James: upon whom my name is called

).

The tent of David is an allusion to the kingly line of David.43 This ruling house fell into ruins at the time of the Babylonian exile (6th cent. BC). But it is now restored in Jesus, a restoration that has opened the door to Gentiles as well as to Jews to seek the Lord. Amos’s words imply that Gentiles as Gentiles, all those over whom my name has been named

(a prophetic allusion to baptism), are fully acceptable to God without conversion to Judaism.44

43 This is how the rabbis also understood it (bSanh. 97a).

44 Some claim that the words from the Gentiles

used in Acts 15 are evidence that Gentile believers should no longer be considered Gentiles, but are now Israelites under the Law (Acts 15:14,19,23). But neither the Greek used here nor the chapter itself supports this interpretation. The decision of the council was to exempt Gentile believers from obligation to the Law of Moses. Gentile believers are called out

not into Judaism but into the kingdom of the Messiah, a kingdom that includes both Jewish and Gentile believers in Jesus as co-equal citizens (1 Pet. 2:9, Eph. 2:19).

It’s important to remember that in David’s historical kingdom there were not only Israelites, but Gentiles of many different varieties: Edomites, Moabites, Ammonites, and others. But of all these many groups of people, the Law of Moses applied only to the Israelite portion of his kingdom. This is the pattern presented in Acts for the believing community. All who accept Jesus as Messiah come under his royal authority. But only the Jewish believers among them are also called to be obedient to the Law of Moses.

The tent of David also brings to mind the tent that David built for the Ark of the Covenant in Jerusalem (2 Sam. 6:17). Here God was worshipped not according to the Law of Moses, which required the Tabernacle of Moses, but according to the instructions of David. The tent of David was an acceptable way to worship God outside the Law of Moses. This is exactly what James and the other Messianic leaders envisioned for Gentile Christians: that they would participate in the worship of the Messiah without coming under the Law of Moses.

James and those with him accepted the prophecy of Amos as proof that it is not necessary for Gentiles to convert to Judaism in order follow Jesus. God has made another way for them through the tent of David, a picture and a type of the ministry of Messiah. And because of that decision, Gentile Christians are not under the Law of Moses today.

The Three Exceptions

But there were three exceptions to this general ruling, three laws of Moses that they decided should be required of Gentile believers: Write to them to keep away from [1] the impurities of the idols,46 and [2] sexual immorality, and [3] what is strangled and blood

(Acts 15:20).47 This may strike you as strange. They had just decided on the basis of prophecy that Gentile followers of the Way are not under the Law of Moses. But then they turn right around and impose three of the laws of Moses on them. What’s going on here? If you look carefully, you’ll see that these are three of the Laws of Noah.48 By requiring these necessary things

(Acts 15:28), the leadership showed its essential agreement with the rabbis of Group B, who did not require Gentiles to convert to Judaism, but did require that they obey the Laws of Noah.49

46 This prohibition appears in Acts 15:29 and elsewhere as things [meat] sacrificed to idols.

47 The prohibition of the meat of strangled animals is closely related to the prohibition of blood: Strangled animals are prohibited because their blood remains in them. Some see the prohibition of blood mentioned here as a fourth exception referring to the prohibition of murder. But its mention together with strangled animals makes this more likely an allusion to Gen. 9:4. Murder itself is prohibited elsewhere in the New Testament (Matt. 19:18).

48 A direct connection between Acts 15 and the Laws of Noah is made in the Apostolic Constitutions 6.3.12 (4th cent.), where both are considered to be part of the Natural Law revealed to all mankind. “Which laws [the three exceptions of Acts 15] were given to the ancients who lived before the law, under a law of nature: Enosh, Enoch, Noah, Melchizedek, Job, and if there be any other of the same sort” (ANF 7.455).

49 In the West, under the influence of Augustine, the three exceptions have been treated as a temporary concession to the Jews rather than as theological necessities. But in the Eastern Church (the Orthodox churches), they are still in force today, having been reaffirmed in the Seventh Ecumenical Council (8th cent.). The Western attitude is often justified by interpreting Acts 15:21 (for Moses...is read in the synagogues every Sabbath

) as the reason why the three exceptions were instituted, in other words, as a concession. But Acts 15:21 is instead explaining why a letter from the council was necessary: to give Gentile Christians an authoritative defense against those in every city

trying to bring them under the yoke of the Law.

But why only these three laws, and not all seven? Many have suggested they were the requirements that most directly affected table fellowship, which was the original source of the conflict (Acts 15:1, Gal. 2:11-21). Uncleanness in any of these areas would make it impossible for Jewish and Gentile believers to sit down and eat together.

But a more likely reason is that the other Laws of Noah were already accepted by the Gentile world. Murder and robbery were also crimes under Roman law, for which courts were established. The prohibition of blasphemy was unnecessary, as blasphemy only took place when the actual name of God was pronounced (YHWH).50 But this pronunciation had become a closely guarded secret, known only to the priests. That left just three of the Laws of Noah to be mentioned: the prohibition of (1) idolatry, (2) sexual immorality, and (3) eating blood, including flesh with blood in it, the same three things commanded by the Council. If Gentile believers stay away from these things, the Council ruled, you will do well

(Acts 15:29). There was no need for them to obey the rest of the Law of Moses, For it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us not to put a great burden on you

(Acts 15:28).

50Sanh. 7:5

Does this mean, then, that these three things are all that are required of Gentile followers of Jesus? Of course not. Gentile believers also share with Jewish believers in Jesus in their obligation to the Law of Messiah, the New Testament, which applies to the entire kingdom of Messiah. Acts 15 only exempts Gentiles from regulations unique to the Law of Moses.51

51 These unique sections include the ritual and ceremonial law. In the area of moral law, there is complete agreement between the Law of Moses and the Law of Messiah. The Ten Commandments, for example, are all repeated in the New Testament (with the exception of the law of the Sabbath, which will be dealt with separately in Part II below). From a technical point of view, though, Gentile Christians are only bound to the Ten Commandments, as to the rest of the moral law, because they are repeated in the Law of Messiah (the New Testament).

Judaizing and Gentilizing

In the decision of Acts 15 and in the writings of Paul, keeping the Law of Moses is considered part of the special calling of being Jewish. Of course a Jewish believer in Jesus will obey the Law, because he is Jewish. And because he believes in Jesus, he will also obey the Law of Messiah. No other alternative is even mentioned in the New Testament for Jewish believers in Jesus.

But for a Gentile Christian to submit to circumcision (in other words, to convert to Judaism and come under the Law of Moses) is a step away from God, rather than toward God (Gal. 5:2,3).52 Why? Because becoming a Jew will not bring a Gentile believer any closer to God than he or she already is in Messiah. Rather, it will take him farther away from God if he thinks that by this he can increase his righteousness. Paul says that such a person has been released [divorced] from Messiah

(Gal. 5:4). He has misunderstood what salvation is all about. Instead, Gentile believers should concern themselves with moving forward in Messiah and the Law of Messiah rather than with coming under the Law of Moses.53

52 I, Paul, say to you that if you are circumcised, Messiah will not benefit you at all

(Gal. 5:2).

53 Several groups today, while affirming the Jewish roots of Christianity, have misunderstood the message of Acts 15, and incorrectly teach that Gentile believers must come under the Law of Moses. This includes the so-called “Messianic Israel” (or Two House Teaching), which claims that Gentile believers are in reality descendants of the Ten Tribes, and must therefore come under the Law of Moses. This ignores the fact that the rabbis themselves ruled the Ten Tribes are Gentiles with regard to the Law (bYeb. 16b, 17a). For more on this topic, see the section on Invalid Attempts at Restoration in Part IV below.

This much historical Christianity has always agreed on. The Christian Church has always condemned Judaizing, which originally meant telling Gentile Christians they must convert to Judaism, or must observe some or all of the Jewish Law in order to be right with God.54

54 Later, Judaizing was incorrectly extended to include observance of the Jewish Law by Jewish believers in Jesus.

But what about the other side, the side of Jewish believers in Jesus? If observing the Law of Moses doesn’t help a Gentile believer draw closer to God, how can not observing the Law help a Jewish believer? It can’t. For a Jewish believer to reject the Law is also a step away from God and from his or her special calling as a Jew. It follows then that if Jewish believers are not allowed to Judaize Gentiles, Gentile believers should also not be allowed to “Gentilize” Jewish believers. Unfortunately, for more than a thousand years that’s exactly what the Christian Church has tried to do to Jewish believers in Jesus: it has tried to force them to become “Gentilized,” sometimes under threat of death for heresy! It wasn’t that long ago that Gentile Christians would give a Jewish believer a ham sandwich to see if he “really” had become a follower of Jesus.

But what if a Jewish believer wasn’t raised observing the Law of Moses? Should he be required to be obedient to the Law? That’s a good question, usually raised by Gentiles. In practice, most Jewish believers want to observe the Law after they accept Jesus as Messiah. The calling of God is irrevocable (Rom. 11:29). Paul circumcised Timothy, even though he was not circumcised before. Why? Because he was Jewish. For a Jewish believer to reject or ignore the Jewish Law is to renounce the covenant of God with his people, to turn his back on his calling. Instead, what does Paul say? Stay in the calling in which you were called (1 Cor. 7:20). If you are circumcised (Jewish), don’t become uncircumcised (a Gentile). If you are uncircumcised (a Gentile), don’t be circumcised (become Jewish; 1 Cor. 7:17-20). Instead, obey the commandments that apply to you (1 Cor. 7:19). For Jewish believers in Jesus, this means the Law of Moses as interpreted and expanded in the Law of Messiah. For Gentile believers, this means the Laws of Noah55 as interpreted and expanded in the Law of Messiah. The Law of Messiah doesn’t replace God’s previous work with mankind, but brings it to perfection.

55 Or if you prefer, the Three Exceptions of Acts 15 or the Natural Law of the Church fathers.

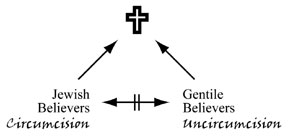

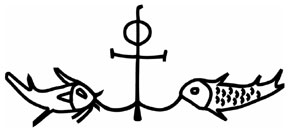

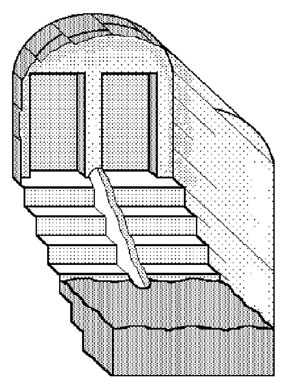

Circumcision and Uncircumcision

This understanding of two distinct groups within the Body of Messiah—Jewish and Gentile—was common in early Christianity. The historical evidence is backed up by archeological evidence: an engraving from the catacombs in Rome shows two fish caught on a cross-shaped hook that looks like an anchor (see diagram above).56 One fish, with scales and fins, is kosher (permitted by the Law of Moses), the other, without scales, is not.57 This image isn’t about fish, of course. It’s about people: two different kinds of people “caught” by the gospel message. The kosher fish represents Jewish believers in Jesus, who continue to obey the Law of Moses; the non-kosher fish represents Gentile believers, who are not under obligation to the Law of Moses. In the New Testament, these two groups are called believers from the circumcision

and believers from the uncircumcision

(Rom. 3:30, 4:9-12, 15:8,9; Gal. 2:7,12; Eph. 2:11; Col. 4:11): two distinct groups within the body of Messiah, each with a different calling, yet united in a common witness to Jesus as Messiah and Lord.58

56 On a marble plaque found in the Catacomb of Domitilla, a burial area identified with early Christians. The two fish and an anchor theme was common in 3rd cent. Christianity, though the two fish are not usually as clearly distinguished as they are here. This drawing is from a photo that appears in Jack Finegan, The Archeology of the New Testament, revised ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton U. Press, 1992), 379.

57 Lev. 11:10,12.

58 Another early artistic representation was of the Jewish and Gentile churches as two women. At the Church of Santa Sabina in Rome, for example, there is a prominent mosaic inscription flanked by two women (5th cent., see illustration below). One is labeled the “Church from the Circumcision” (Eclesia ex Circumcisione) and the other the “Church from the Gentiles” (Eclesia ex Gentibus). This is evidence that the original two-fold nature of the Church was still remembered in the 5th cent. (Finegan, Archeology, xli.). These same two women can be seen in a 4th cent. mosaic at the Church of Saint Pudentiana in Rome. Here they are crowning Paul for his mission to the Gentiles and Peter for his mission to the Jewish people. Elsewhere, the depiction of Peter and Paul itself served to represent the two-fold division of the Church, as in the triumphal arch of Sta. Maria Maggiore in Rome (5th cent.). Here the two apostles are associated with two cities, Jerusalem and Bethlehem, which came conventionally to represent the Jewish and Gentile churches. Bethlehem was associated with the Gentiles because of the visit of the Gentile magi (the “wise men”) at the time of Jesus’ birth. This convention of the two cities representing the two branches of the Church can also be seen above the apse of the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna (6th cent.).

This unity transcends the differences between Jew and Gentile: both have access in the same Spirit to God the Father (Rom. 1:16, 2:10). And because of this, the barriers between Jew and Gentile have been broken down. Even though we are different, we have peace between us because of our unity through the death of Jesus. There are different callings, but one body of Messiah. And just as different spiritual gifts are necessary for the proper functioning of the body, both Jews and Gentiles are necessary for proper balance in the body of Messiah. This is the one new man

vision of Paul in Ephesians: For he himself is our peace, who made both [Jews and Gentiles who believe in him] one, and destroyed the dividing wall…that in himself he may create out of the two one new man

(Eph. 2:14-15).59 Gentile believers need Jewish believers to connect them with their Jewish and Biblical roots. Jewish believers need Gentile believers to interpret those roots and teach them to the peoples of the world. Working together, we can extend the spiritual impact of Israel—and Israel’s Messiah—to the ends of the earth.

59 Or as taught by the earliest church: “Through the extension of the hands of a divine person [Jesus on the cross] gathering together the two peoples to one God” (Irenaeus, Against Heresies 5.17.4, 2nd cent., ANF 1.545). This saying is attributed to “a certain man among our predecessors,” which takes it back to the generation after the disciples.

CHAPTER 2:

AFTER THE BOOK OF ACTS

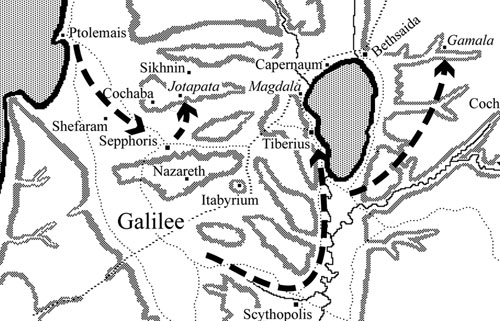

War with Rome

Unfortunately, Paul’s one new man

vision was never fully realized in the body of Messiah, except perhaps in the first generation or two. Because soon after the time of Paul, while the New Testament was still being written, history began to make bitter enemies of Jews and Gentiles. This took place through a series of wars and revolts that drove a deep wedge between the two.60

60 Paul died, according to tradition, in the persecution of Nero in AD 64, two years after the end of the events recorded in the Book of Acts. The First Jewish Revolt began in AD 66. The New Testament was completed in about AD 95.

The first of these wars broke out in AD 66, only four years after the end of the events recorded in the book of Acts: the First Revolt of the Jews against Rome.61 It started with street fighting between Jews and Gentiles in Caesarea, the same city where God first poured out his Holy Spirit on the Gentiles at the house of Cornelius (Acts 10:44-46, 15:8,9). The resulting strife quickly spread to Jerusalem where Gessius Florus, the Roman governor, plundered the Temple treasury and committed acts of aggression against the people.62 In response, the sacrifice offered in the Temple on behalf of the emperor was cancelled.63 This was the first act of open rebellion. Before long, the entire city was in revolt. Several Romans soldiers were killed.

61 The spark that ignited the conflict was the intentional desecration of a synagogue in Caesarea on the Sabbath by sacrificing birds at the entrance to the building. Josephus, Wars, 2.14.5 (289).

62 Florus was the 9th Roman governor after Pontius Pilate (AD 26-36), the 2nd after Felix (52-60) and Festus (60-62), both mentioned in the book of Acts (Acts 23:24, 24:27).

63 Wars 2.17.2 (409).

In response, the Gentiles in Caesarea rose up against the city’s Jewish inhabitants. Twenty thousand Jews were killed—almost all the Jews in the city.64 This roused the whole country to rebellion, and ignited conflicts between Jews and Gentiles throughout the region. Tens of thousands were killed.65 Most of the Jewish dead, 50,000, were in Alexandria, the second largest city in the Empire. Here Roman soldiers attacked a Jewish residential area.66

64 Wars 2.18.1 (457).

65 In Syria, this included many “Judaizers.” Among these were likely Gentile Christians, who were suspected by both sides (Wars 2.18.2 (463).

66 Wars 2.18.8 (497). This Egyptian city with its large Jewish population is likely where Jesus and his parents had stayed after they escaped Herod’s attack on the infants of Bethlehem (4 BC, Matt. 2:13-15).

The Roman governor of Syria, Cestius Gallus, marched to Jerusalem to restore order, but retreated with heavy losses. Now there was no turning back. The Jews set up a revolutionary government and built up their defenses as quickly as they could. But there was little hope against the huge Roman army.

Ironically, the Jewish will to fight was encouraged by some of the same Messianic prophecies that point to Jesus as the Messiah.67 But while Jesus placed the realization of an earthly Messianic kingdom far in the future (the end will not take place immediately,

Luke 21:9), others used these prophecies to stir up the resistance to Rome.68

67 Another factor that encouraged them was their hope for assistance from the Parthian Empire in Persia, the eastern enemy of Rome. But this hope never materialized. Philo, Embassy to Gaius 31 (216).