Neglected Issues in the Debate About the Millennium

by Jeffrey J. Harrison

The Millennium—the thousand-year reign of Messiah— was the hope of the earliest Church. It was the longed-for time of restoration of all things

in which the earth would be restored to its pristine state: the regeneration

as Jesus called it, a word which in the original Greek means Genesis again

(Acts 3:21, Matt. 19:28, Rev. 20:1-6). Yet over the years, the Millennium became one of the most hotly debated of all end-time topics, rejected by many after Greek thinking (Platonism) became dominant in the Church. This rejection is still maintained by many. But there are two important issues that are often neglected in considering differing views about this end-time period. One is an unpleasant link with anti-Jewish beliefs; the other a false claim to represent the views of the earliest Church.

The most popular view about the Millennium, held by most churches through a large portion of church history, has been the amillennial (no Millennium

) view. This understanding, still popular in traditional churches today, rejects the idea that the Millennium will take place after the return of Jesus. Instead, it teaches that the thousand years, either literally or symbolically, takes place before the return of Messiah. This was the nearly unchallenged position of the Western Church for more than a thousand years, once Augustine of Hippo adopted it in the 5th century AD.

But the amillennial position has a disturbing anti-Jewish history. Its roots go back to the Alogoi in the second century.* This group in Rome rejected the book of Revelation and its teaching of the Millennium, going so far as to claim that the book was written by the heretic Cerinthus.** To their taste, the idea of an earthly Millennium with the Messiah ruling from Israel was simply too Jewish,

glorifying Israel and the Jewish people in a way that was unacceptable to a growing anti-Jewish element within the Church. This rejection of the Millennium became widespread after the Council of Nicea, which incorporated anti-Jewish ideas into Church law.

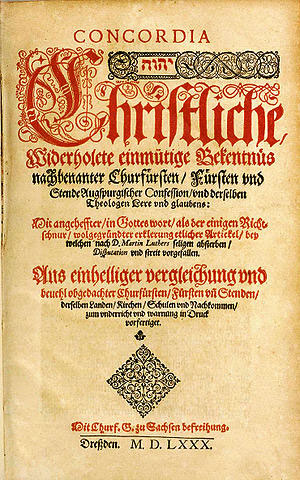

which includes the Augsburg Confession

* Earlier amillennialists are mentioned by Justin Martyr, but nothing more is known of their beliefs (Dialogue with Trypho 80).

** A view mentioned by Eusebius, the influential church historian of the 4th century. He also had doubts about the book, as did others of his generation, proposing instead that the author was a different John than the apostle (Ecclesiastical History 3.25,39; 7.25). But this was because he, too, had spiritual

(actually Hellenizing) and anti-Jewish objections to Revelation.

This connection between anti-Jewish thinking and amillennialism continued right up into the Reformation period. The Lutheran Augsburg Confession (article 17) condemned as Jewish

the belief in a literal Millennium. So, too, the Reformed Second Helvetic Confession rejected the Jewish dream of a Millennium, or golden age on earth, before the last judgment

(chapter 11). It was only in the 19th and 20th centuries that millennial beliefs became widespread among Christians again.

Many modern amillennialists have adopted this position out of intellectual frustration with the second most popular view: dispensationalism. This is a version of premillennialism (the belief that Jesus will return before the Millennium

) that is strongly promoted in many conservative Protestant churches. I, too, shared this frustration. The dispensational teaching that there will be marriage and the begetting of children in the Millennium directly contradicts the teaching of Jesus (Matt. 22:30, Luke 20:35), and was one of the main reasons that an earlier version of premillennialism was rejected by Augustine and others.

The dispensational teaching that in the Millennium, glorified saints (in resurrection bodies) will rule over fleshly sinners (in earthly bodies) sounds too much like the Inquisition to me—not to mention the even more bizarre idea of multiple resurrections (or raptures) of believers at different times. Those left behind

because of their lack of faith, as in the popular book and film series, experience what is in effect a new Protestant version of Purgatory.* But there is another, much more Biblically consistent possibility: a form of premillennialism without these dispensational excesses, as was held by the earliest Church.

* Purgatory is the unbiblical teaching of a time of punishment after death that will purify baptised sinners for heaven. In a very similar way, dispensationalism claims that carnal

Christians will not participate in the resurrection at Jesus’ initial appearance, but will instead be left behind to be purified by suffering. After that, they will experience a later, additional resurrection (or one of several additional resurrections). But the Bible clearly teaches a single resurrection for the righteous, referred to over and over again as the resurrection (Matt. 22:28, 22:30, 22:31, John 11:24, Acts 4:33, etc.). In Luke 14:14, Jesus specifically calls it the resurrection of the righteous.

This will take place at Jesus’ return (1 Cor. 15:13). There will also be a single resurrection of the wicked (John 5:29, Acts 24:15), though after the Millennium (Rev. 20:13).

Who Will Survive the Return of Messiah?

(Exclusive Brethren)

Dispensationalism dates back to the Darbyites of the 19th century. They helped popularize the belief in a literal Millennium after more than a thousand years of the suppression of this idea. This was a remarkable accomplishment. But they packaged this belief with ideas that were contrary to the teachings of the earliest Church. One of the most glaring differences concerns the destruction of the wicked that will take place at the return of Jesus. Dispensationalists teach that this destruction will affect only the armies gathered against Jerusalem. As a result, many non-believers, they say, will survive Jesus’ return, living under the rule of the saints (the Inquisition-like view mentioned earlier). But in spite of claims to the contrary, this was not the view of the earliest Church, or of Jesus himself.

When Jesus taught about his return, he compared it to the Flood of Noah: And just as it happened in the days of Noah, so it will also be in the days of the Son of Man

(Luke 17:26, also in Matt. 24:38-39). Dispensationalists focus their attention on the sudden and unexpected nature of Jesus’ return (Luke 17:27). But there’s an additional point that Jesus is making here with just as much force: and the Flood came and destroyed them all

(Luke 17:27). Not only will his coming catch the world by surprise: it will result in the destruction of everyone left on earth, just as in the Flood of Noah. Only a remnant will be preserved, caught up in the clouds to meet the Lord (1 Thess. 4:17; this is the resurrection of the righteous or as some call it, the rapture

). All the rest will die.

In Luke, not only the Flood, but also the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah is used to illustrate the destruction to come (Luke 17:26-30). The fire and brimstone coming down from heaven destroyed them all

(Luke 17:29). As Jesus immediately continues, It will be just the same on the day that the Son of Man is revealed

(Luke 17:30). The point, again, is that all who are left on the earth will die.

But even that’s not the end of it. Jesus continues to make the same point in his description of the separation of the righteous and the unrighteous at his return: One will be taken along, the other will be left behind

(Luke 17:34-36). When the disciples ask, Where, Lord?

Jesus replies, Where the corpse is, there will the vultures also be gathered

(Luke 17:37, an allusion to Ezekiel 39:17-20). His message? Those left behind will die in the destruction of the wicked. The idea that many or even most of those left behind will survive to have a second chance

at salvation contradicts Jesus’ own clear teaching.

This is also the point of Jesus’ parable of the ten virgins (Matt. 25:1-12). When the Messiah (the bridegroom) comes, he gathers the faithful (the five wise virgins), and the door is locked behind them (Matt. 25:10).* Here, too, there is no second chance for those left behind (Matt. 25:11-12).

* The verb kleio that appears here is often translated shut,

but its derivation from the noun kleis (key

) indicates its primary meaning: locked.

The book of Revelation confirms the idea that all the wicked will die at Messiah’s return. In Revelation 19, the birds flying over the battlefield come to eat the flesh, not only of slain kings and warriors, but the flesh of all people, both free and slaves, and small and great

(Rev. 19:18). The qualification of all people

by the words both free and slaves, and small and great

makes it as clear as possible that all people

here means exactly that: all the people remaining on the face of the earth will die. (This passage is an intentional allusion to Jesus’ own teaching, as in Luke 17:37 mentioned above.)

Who Will the Saints Reign Over?

Many have been thrown off by Rev. 20:3 and its description of the binding of Satan, that he might not deceive the nations any longer until the thousand years are finished.

They assume this implies that the unbelieving nations continue to exist in the Millennium. But the verse doesn’t say that. It simply says that Satan’s days of deceiving people (the word nations

can also be translated Gentiles

) are over for a thousand years.

Another stumbling block is the statement that the saints will reign with Messiah during the thousand years (Rev. 20:4,6). Many assume that this, too, means there will be unbelievers around for the righteous to rule over. But is Messiah’s reign limited to people? He rules over stars, planets, and galaxies, as well as angels and earthly creatures of every variety. The Bible specifically says that the saints will judge angels (1 Cor. 6:3).* Millions of believers will also need some form of government (Luke 19:17,19). Nothing in these verses requires there to be unbelievers in the Millennium; in fact, quite the contrary: how then would this be a time of blessing? (Rev. 20:6) It would be just like the present age of the earth, with sinners constantly grieving the heart of God and the saints.** Rather, as Commodianus, an early Christian writer (3rd cent.) put it: But from the thousand years God will destroy all those evils

(Christian Discipline 44).

* In Biblical thinking, the one who judges is the one who rules.

** Some claim that every knee will bow

(Phil. 2:10) is a description of nonbelievers on earth being forced into submission to Jesus in the Millennium. But in that same verse, those who bow the knee include not only those on earth, but those who are under the earth.

These are the nonbelievers who in death are excluded from the Millennial blessings on earth.

The Resurrection of the Unrighteous

Nonbelievers don’t show up again until the end of the thousand years, at the time of the resurrection of the unrighteous. This takes place when Satan is released from prison (Rev. 20:5,7). This second resurrection is described in Revelation 20:9, when it says that the wicked dead ascended to the surface of the earth,

coming up with Satan from the pit.* This second resurrection is where the nations of Gog and Magog come from that are introduced in the previous verse (Rev. 20:8).**

* Vs. 9 doesn't say they marched across

as in the NIV, or they marched up over

as in the NRSV, or they swarmed up over

as in the Amplified Bible—all of which take considerable liberty with the text—but rather that they came up

or they went up

as in the NASB and KJV. The Greek literally says they ascended to the breadth of the earth

—as opposed to the confines of the pit.

** John first describes what is going to take place using the future tense in vss. 7 and 8. He then brings us into the action using the past tense in vss. 9 and 10. Using a summary statement like this to introduce the following section is a common technique in the Bible.

This gives us a radically different picture of the end-time battle of Gog and Magog than that envisioned by dispensationalists (Rev. 20:7-10). They typically teach this to be a war between glorified saints on one side and fleshly unbelievers on the other. But this wouldn’t be much of a battle. Resurrection bodies will be invulnerable; the flesh of earthly men is not. Rather the battle of Gog and Magog is between resurrected saints on one side and resurrected sinners on the other: a truly awe-inspiring and threatening challenge that only the awesome power of God can overcome (Rev. 20:9).

The resurrection of the unrighteous at the close of the Millennium also resolves another issue: that of God’s justice. Without this last chance at earthly existence, the guilt of individual sinners might be disputed. Claims could be made for eternity that God wasn't fair in his judgment. But in the titanic end-time battle of Gog and Magog, the guilt of all sinners will be clearly established beyond any doubt. For after being raised from the dead, they will choose to fight directly against Jesus himself and against his chosen people. This will show to all that their judgment is just.