Crossing the Red Sea

and the Route of the Exodus

by Jeffrey J. Harrison

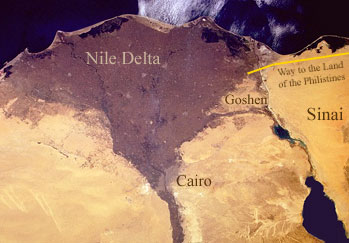

In Egypt, the children of Israel lived in the region of Goshen, an area good for sheep and shepherds along the eastern edge of the Nile Delta, about 100 km (60 miles) or so northeast of Cairo. East of Goshen stretches the barren desert of northern Sinai, one of the most inhospitable deserts on earth. This is a sandy desert, like those in the movies, with huge sand dunes moving at the whimsy of the wind, sometimes burying standing palm trees, and then weeks or months or years later moving on again.* The skies are often clear, especially in the summer, and the temperatures soar. Summer average monthly highs in Sinai reach 41° C (106° F), so hot that an air-conditioned tour bus can only with difficulty make it bearable. At night, especially in the winter, the temperature can plummet below freezing.

* These dunes can reach a height of 27 m (90 feet). This is completely unlike the deserts of Israel or of southern Sinai, which are rock deserts, with comparatively little or no sand accumulation.

When the wind is from the east, it can come howling across Sinai into Egypt, bringing airborne dust with it. This is the same east wind mentioned in the plague of locusts, the eighth plague to strike Egypt in the time of Moses (Exo. 10:13). In a plague of locusts, huge dark clouds of hungry insects land on the green fields, something that still happens every few years today. This same east wind may also have brought the ninth plague, the plague of darkness that the Bible says could be felt

(Exo. 10:21). This likely refers to wind-borne dust. One of the soils found in the deserts of the Middle East is called loess soil, a very fine, dust-like soil the consistency of talcum powder. The wind can carry it thousands of meters into the sky where it can remain for days. If there’s enough of it, it can turn the sky dark. This may also be what happened when Jesus was on the cross, when the sky grew dark for three hours (Matt. 27:45).

The next plague, the tenth and final plague, was the plague of the first-born. This was the plague for which the children of Israel had to prepare a lamb and smear its blood on their lintels and doorposts—the original Passover—pointing prophetically to a yet greater deliverance, that of the cross of Calvary.* That same night, a mourning Pharaoh sent the Israelites out to begin their journey to the Promised Land (Exo. 12:30-31,42).

* In Christian tradition, the smearing of the blood on the lintel and doorposts was understood to make (or to foreshadow) the sign of the cross.

To get to Canaan (modern Israel), they had to cross the forbidding deserts of Sinai. This was no easy task, even for the Bedouin who live in the desert. Moses had a huge group of several million people with him, most of whom had never been in the desert before. How would they survive? How would they find food and water for so many, as well as for the flocks and herds they brought with them?*

* The tremendous logistical difficulties in crossing Sinai are neglected by the recently popular theory of a Red Sea crossing into Arabia through the eastern branch of the Red Sea (as proposed in The Gold of Exodus by Howard Blum; also the books and tapes of Ron Wyatt, Larry Williams, and Bob Cornuke. See our review of The Search for the Real Mt. Sinai). The relatively short desert journey to the turqoise mines at Serabit el-Khadim—only 150 km (100 miles) east of Cairo—was undertaken by the Egyptians with trepidation and extensive preparation. How much more to enter the desert interior! Tremendous miracles of provision would have been necessary, both for the army of Pharaoh as well as the children of Israel. But such miracles are mentioned only after the sea crossing. This popular theory also abandons the clear chronology of Exodus itself, that places the sea crossing after three days of travel (in Exo. 12-14, and confirmed by Num. 33:5-8). A minimum of seven days was required to cross northern Sinai along a coastal route well-provisioned with water and supplies. How much more would have been necessary for the difficult crossing through central Sinai, where there were no prepared provisions and the real possibility of encountering hostilities from local tribes (as Moses and the Israelites faced at the hands of the Amalekites; Exo. 17:8-16).

From a spiritual point of view, the start of their journey is like the moment when someone first accepts Jesus as Messiah and is set free from the bondage of Satan. At first, they experience only the joy and the excitement of their new-found freedom. But before long, we notice that God is taking us a way we’ve never been before, a foreboding, dangerous-looking way. What will we eat? How will we survive?

The shortest route to Canaan was the road along the north shore of Sinai, near the Mediterranean Sea. But this was well guarded with Egyptian forts and troops which, if they went this way, would surely lead to fighting (Exo. 13:17). Nor could they go straight east. That would bring them into the dangerous desert of northern Sinai. The only other alternative was southeast to Southern Sinai, where water could be found here and there in wells and springs. This was a much longer route. But it was the only realistic way to go (Exo. 13:18).*

* The alternative of a northerly route for the Exodus must be rejected in light of God’s explicit instructions to Moses to avoid going this way (along the way to the land of the Philistines,

Exo. 13:17). Even if they left the road to travel cross-country, there was the difficulty of travel through the shifting sands of the north. Central Sinai, a rock desert, was more passable. This can be seen in the Darb el-Hajj route once used by Egyptian pilgrims going to Mecca. But these pilgrims were unencumbered by flocks and herds, for which there is no pasturage in this desert wasteland. Only to the south would the children of Israel find adequate, though sparse, pasturage for the extensive flocks they brought with them. Historical support for this southern route can be found in Papyrus Anastasi V, a record of other Egyptian slaves who escaped in this same southerly direction.

The first day’s journey took them about twenty miles southeast to Succoth, near the modern city of Ismailia (Exo. 12:37). This wasn’t so difficult. It took them through a desert to be sure, but they started and ended the day in well-watered areas: Succoth is in the Wadi Tumilat, the last section of inhabited land before the deep desert. Beyond that to the east lay the desert of Shur, which stretches out like a wall protecting Egypt on the east.

The next night they camped in Etham, right at the edge of the desert (Exo. 13:20). If they continued straight east, there would be no water for days. Here, at Etham, is the first mention of the pillar of cloud and fire, God’s presence with them, which would be sorely needed in the days ahead (Exo. 13:21-22).

But instead of continuing into the desert, God instructed Moses to circle back to Pi-hahiroth, at the western edge of the Bitter Lakes (the sea,

Exo. 14:1-3).* If you look at this area on a satellite map, God’s strategy makes perfect sense: it follows the only tiny strip of watered land going south. But to Pharaoh, this doubling back looked as if they had become lost and were wandering aimlessly, or were perhaps frightened of the desert.**

* The Bitter Lakes is the name of a two-lobed lake that is today part of the Suez Canal. Other suggestions for the Red Sea (actually called the Reed Sea

in Hebrew) include nearby Lake Timsah, which seems too small, and the northern tip of the Gulf of Suez (the traditional site). A Gulf of Suez crossing has claimed recent support from experiments with a scale model of the seabed and wind provided by a hair dryer. But the tiny channel opened up in the experiment was anything but dry land

(Exo. 14:16,21-22, etc.). It was also too narrow to fit the story (see below), not to mention that the Gulf lacks the necessary reeds. (Sea

in Hebrew can be used for any sizeable body of water.)

** Camping on the western side of the Bitter Lakes certainly made them appear trapped: to the east was the lake, to the south was a desert mountain, Baal-zephon, to the west another desert. This made it look easy for Pharaoh to capture them (Exo. 14:6-9). But in fact, God was preparing a trap of his own.

When Pharaoh changed his mind and came after them, just imagine how the Israelites felt. In the distance they could see the dust ascending as their old slave master and his army advanced across the desert (Exo. 14:10). After only three days of freedom, their past was about to catch up with them with a vengeance. They began to think, and to say, that it would have been better never to be set free, to stay a slave in Egypt, rather than face a fight with Pharaoh’s army (Exo. 14:11-12).

But while victory in our own strength is often impossible, we can win when someone else is involved in the fight, whose ability is infinitely greater than our own. As Moses put it, Don’t fear! Stand strong and see the salvation of the LORD

(Exo. 14:13). Or as Paul says in Eph. 6:13-14: Stand, therefore

in the evil day.

Or as James puts it: Resist the devil and he will flee

(James 4:7). Or again as Moses goes on to say: The Lord will fight for you while you keep silent

(Exo. 14:14).

When the plagues struck Egypt, all they had to do was put the blood of the lamb on the doors of their homes. As with Christians, when we mark our lives with the blood of the Lamb, God sets us free. But that’s not the end of the war. It’s only the first battle, when we make Satan an enemy. Later, he comes to attack us in force, while we’re still weak, a little uncertain, and facing the unknown. That’s when we need to stand strong and see the salvation of the Lord.

The people weren’t the only ones worried. Moses himself must have been crying out to God, too, since God says to him, Why are you [speaking in the singular to Moses] crying out to me?

(Exo. 14:15) Moses had faith that God would deliver them. But he had not yet stepped out, trusting in that deliverance. So God told him to Tell the sons of Israel to go forward

(Exo. 14:15). They had to step out in obedience to God, and then God would do his part.

Just then the pillar of cloud, directed by the angel of God,

moved behind them, coming between the Israelites and the Egyptians (Exo. 14:19-20). This is the first we hear that the Angel of the Lord was with them. This is the same angel that God later says has the power to judge them (obey his voice; do not be rebellious toward him, for he will not pardon your transgression

). How does an angel have such authority? Because God’s name,

that is to say his personal presence, is in him

(Exo. 23:20-21).

The Biblical interpretation of this angel and of the pillar of cloud and fire is given in Revelation 10. Here John sees a mighty angel clothed with a cloud, whose feet are like pillars of fire—imagery that directly connects him with the angel of the pillar of cloud and fire in Exodus (Rev. 10:1). But Revelation goes on to identify this angel as divine: a rainbow appears over his head as in Ezekiel chapter 1, where he speaks and acts as God (Eze. 1:28, 2:4; compare Rev. 4:3 where the rainbow appears over the throne of the Father). He is also identified with Jesus: his face shines like the sun just as Jesus’ face did at the Transfiguration (Matt. 17:2). He is clothed with a cloud, just as Jesus said he would be at his return (coming in a cloud,

Luke 21:27). And he roars like the Messianic Lion of Judah (Gen. 49:9). The angel of God

that came to their rescue in the desert is the Son of God, the arm of the Lord, the angel of the Lord—by whatever name you would like to call the one whose very name means salvation.

* (Exo. 14:19) He is the mighty hand and outstretched arm

by which God sets his people free (Deut. 4:34, 5:15)!

* Jesus, Yeshua in Hebrew, means salvation.

This is one of the many pre-incarnate appearances of the Son of God in the Hebrew Scriptures (the Old Testament).

When Moses stretched out his own hand over the sea, the wind began to blow—an east wind, coming from the desert (Exo. 14:21). It blew all night long, forcing the water right out of the lake bed. This is what the words of verse 21 actually say: And the Lord caused the sea to go back by a mighty east wind all

night, and he made the sea dry land

(Exo. 14:22). There is no mention of a narrow pathway opening up through the sea as is often pictured in religious art and movies. This would be impossible based on the logistics of the crossing: for a couple of million people to file through single file or even in several lines would have taken days if not weeks. Only if the gap was at least 5 km (3 miles) wide could they have crossed in a single night.*

* This is according to a report attributed to the Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army. The Bible says only that the waters were a wall to them on their right and on their left

(Gen. 14:22). The Bible gives no indication of how far apart these walls of water were. But this verse can also, and probably should be translated: the waters were a wall to the south and to the north of them.

If so, the meaning is that the blown-back waters protected them—like a wall—by preventing Pharaoh’s army from going around to the north or to the south of the lake bed.

This was not the only time such a thing had ever happened. A similar event is recorded in a story dating all the way back to the Egyptian Old Kingdom period, in which the water of a lake piled up on one side, laying bare the rest of the lake bed, before rushing back again.* There are also modern reports of the wind pushing back the water of these desert lakes.**

* William Kelly Simpson, et al, Third Tale: The Marvel Which Happened in the Reign of King Snefru,

in The Literature of Ancient Egypt, 3rd ed. (New Haven: Yale U. Press, 2003), 16-18. Snefru reigned in the 4th dynasty. From a papyrus copied in the Hyksos Period.

**Ali Shafei, Bulletin de la Societe royale de Geographie d’Egypte, XXI [1946], p. 278 in K. Kitchen, Red Sea,

in The Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1976), 47.

Some have rejected the Bitter Lakes as the site of the crossing, claiming the water was too shallow. But water levels in recent years do not necessarily indicate levels in the past. The water found in the lakes of arid regions can vary dramatically from year to year and from season to season. But it wasn’t just the depth of the water that killed the Egyptians—surely some of them knew how to swim! Rather it was the force of the sediment-laden flood waters as they rushed back into the lake bed, creating deadly undertows and whirlpools as they washed together. This same force has been the cause of the damage in other, much more recent floods around the world that have destroyed homes and lives.

The morning watch

in which God released the waters against the pursuing Egyptians was the last watch before dawn, between about 3 am and 6 am (Exo. 14:24-25). By sunrise all the army of Pharaoh was destroyed (Exo. 14:27-28). What an amazing experience of deliverance for the children of Israel!

Paul describes this experience, with its total victory over the enemy, as a picture of Christian baptism: that they were baptized...by the cloud and by the sea

(1 Cor. 10:1-2). This reflects the belief of the early Christians that baptism was an empowerment to live a sinless life, with total victory over Satan!

For the Israelites, it was also a kind of resurrection, going from what seemed like certain death at the hands of Pharaoh to new life. So, too, Paul says, we are baptized into Jesus’ death in order to rise up in newness of life (Rom 6:3-7). We have died to the slavery of sin, and risen to follow the Angel of God out into the unknown. This is a new way of life, in which our own strength is not enough. But if we keep our eyes on Jesus, we can trust him to lead us to the Promised Land.